In Defense of Bias

AI Bias Is Not the Problem. Inexplicability Is.

One of the most corrosive trends in our AI discourse isn’t technical — it’s linguistic.

Phrases like “to protect our humanity, humans should always be in the loop” get thousands of likes because they sound wise. They’re not. Humans do not need to manually drive cars to preserve their humanity. These phrases offer comfort rather than insight.

This kind of slop (what I’m calling linguistic imprecision) is fueled by algorithms that reward banality, the genuine complexity of AI, and something older and subtler: the slow degradation of meaning itself.

It’s causing us to misunderstand (and vilify) essential parts of AI.

Denotation vs Connotation

When you do something the wrong way enough, it can start to feel like the right way. It’s as true in seasoning food — I grew up in a household that didn’t cook with salt or butter, which I now see is insane — as it is in language. In fact, there are terms to explain this lexical phenomenon: “denotation” describes what a word means, and “connotation” describes what people want it to mean.

Connotation doesn’t just change how we use words it changes how we understand the world through them.

Terms like “ignorance,” “activist,” “liberal,” and “conservative” are rarely used to denote their literal definition. They’re used to connote a figurative definition, in many cases as a pejorative (a word expressing contempt or disapproval).

“Bias” is another such victim of connotation. It has become a nasty word, used to describe behavior like unfairness, meanness, or even bigotry. As early as the 16th century, people used it to describe “undue prejudice” in the legal system. By the early 20th century “bias” was the barb cast at publications and reporters that readers felt (fairly or unfairly) didn’t meet the new standard of objective journalism. In the latter half of the 20th century, the rise of social sciences spread the term into everyday social life, recasting it as a quasi-diagnostic flaw.

But bias is, by definition, “a tendency, inclination, or prejudice toward or against something or someone.” It is, denotationally, a neutral term.

Today, when we hear someone use “bias,” especially if they accuse someone else of it, we can safely assume acrimony: the coach who doesn’t put your child in the game enough, the teacher who grades an essay harshly, the banker who doesn’t approve your loan — they’re all biased.

We don’t hear bias given credit when parents take care of their children (“good parenting” rather than a “bias for care”), when people are nice (“kind souls” vs “biased for warmth”), or when others pick up litter in public places (“acting like a Boy Scout” instead of “biased for civic duty”). Doing good is driven by a bias to do good.

Bias is essential. For humans and for AI.

But the distance between its connotation and denotation is having a major effect on one of the most important issues in AI, and leading many people to believe bias is something that should be eliminated.

Bias as the Basis of Agency

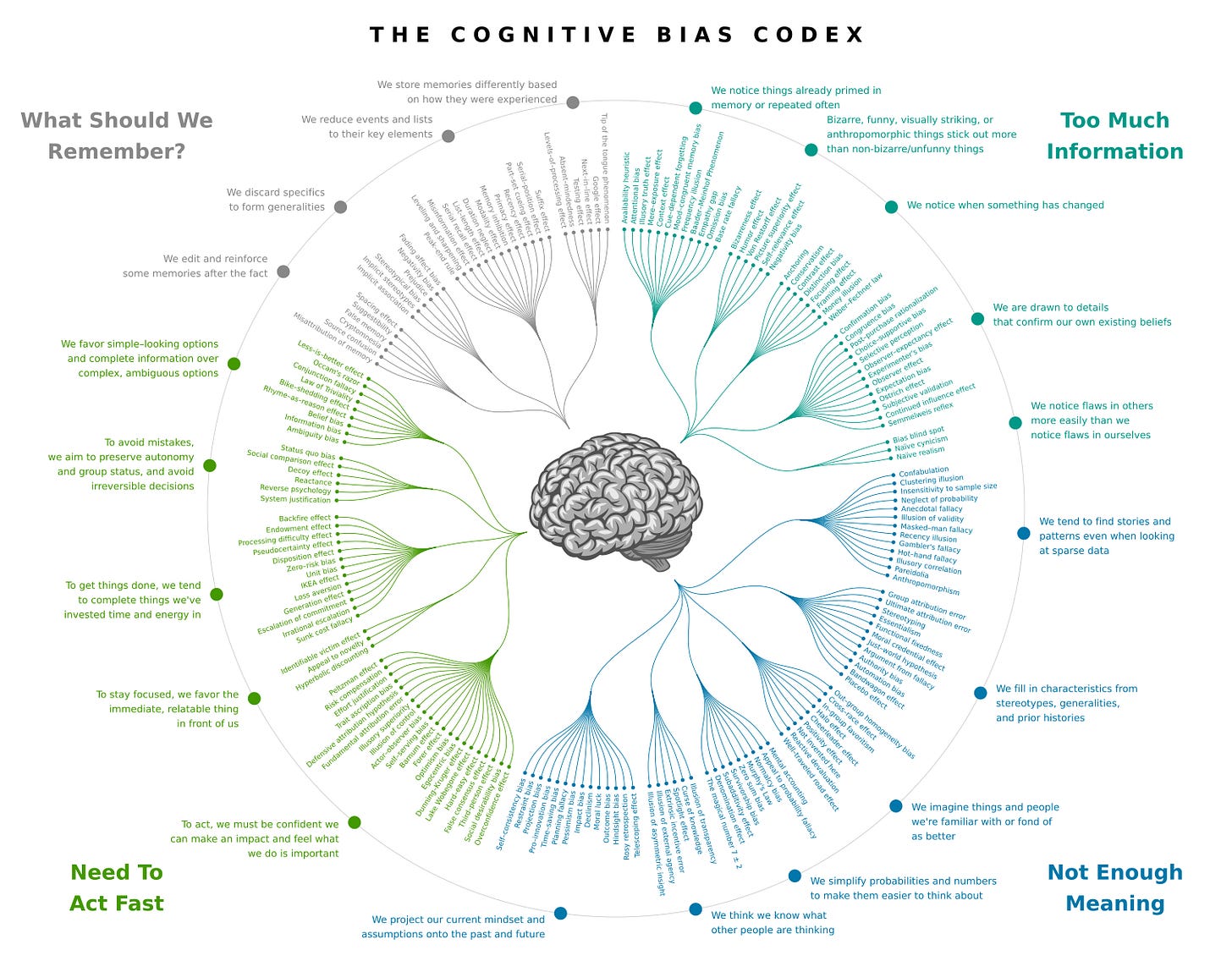

Biases are not defects in human cognition; they are its foundation.

Humans are able to operate in the world because biases turn all our lived experiences and genetic predispositions into a series of impulses (both good and bad). They are the mental frameworks that allow us to quickly and efficiently turn inputs, wants, and needs into thoughts and decisions. They allow us to move through the world with agency, rather than pinballing through it like passive zombies overwhelmed by stimuli.

These cognitive shortcuts give us, in a moment, access to a lifetime’s worth of insights, while protecting us from memories we don’t actually want to consider when we contemplate what flavor ice cream to get.

In AI, “bias” was adopted early as a technical term, along with “weights,” to describe how and what the machine considers and prioritizes when making a decision. My first boss, Lukas Biewald, is actually the CEO of a company aptly called Weights and Biases (recently acquired by CoreWeave), which helps developers build and manage their AI models.

In humans and machines, biases also allow us to work toward the goals we want (what Ziva Kunda calls motivated reasoning), and create strategies for taking action with incomplete information and uncertain futures, “A biased mind can handle uncertainty more efficiently and robustly than an unbiased mind.”

The complication for humans, though, is that we can’t fully see or explain our biases. Every single thing we have ever experienced informs them, and it is all buried beneath trillions of neurons in our brain and nervous system. There is not enough therapy in the world for any individual to fully appreciate or unravel the rat’s nest of how they formed.

This is why seemingly rational people can do irrational things, and why we often lack answers to the questions “Why did I do that?”, “Why do I feel this way?”, and “What was I thinking?”

Moreover, even if we could make sense of everything we believed, we would never admit most of it. A cop won’t tell you they’ve pulled you over because they’re going through a messy divorce, and a waiter won’t tell you they recommend the meatballs because it makes the restaurant smell like their childhood home.

We move through the world with an unspoken understanding that our deepest motivations are often unknowable (though Freud argued otherwise) and many of the known ones (both good and bad) are far too intimate to share.

This leads to one of the stranger elements of the human experience: the fundamental inexplicability of everyone’s decisions (including our own).

Solving the Explainability Problem

When people ask me, “How do we remove bias from AI?” they usually mean one of two things:

How do we stop machines from amplifying injustice?

Or, more often, How do we make machines agree with my values?

What they should be asking is, “How do we build an explicable machine?”

We all want AI models that:

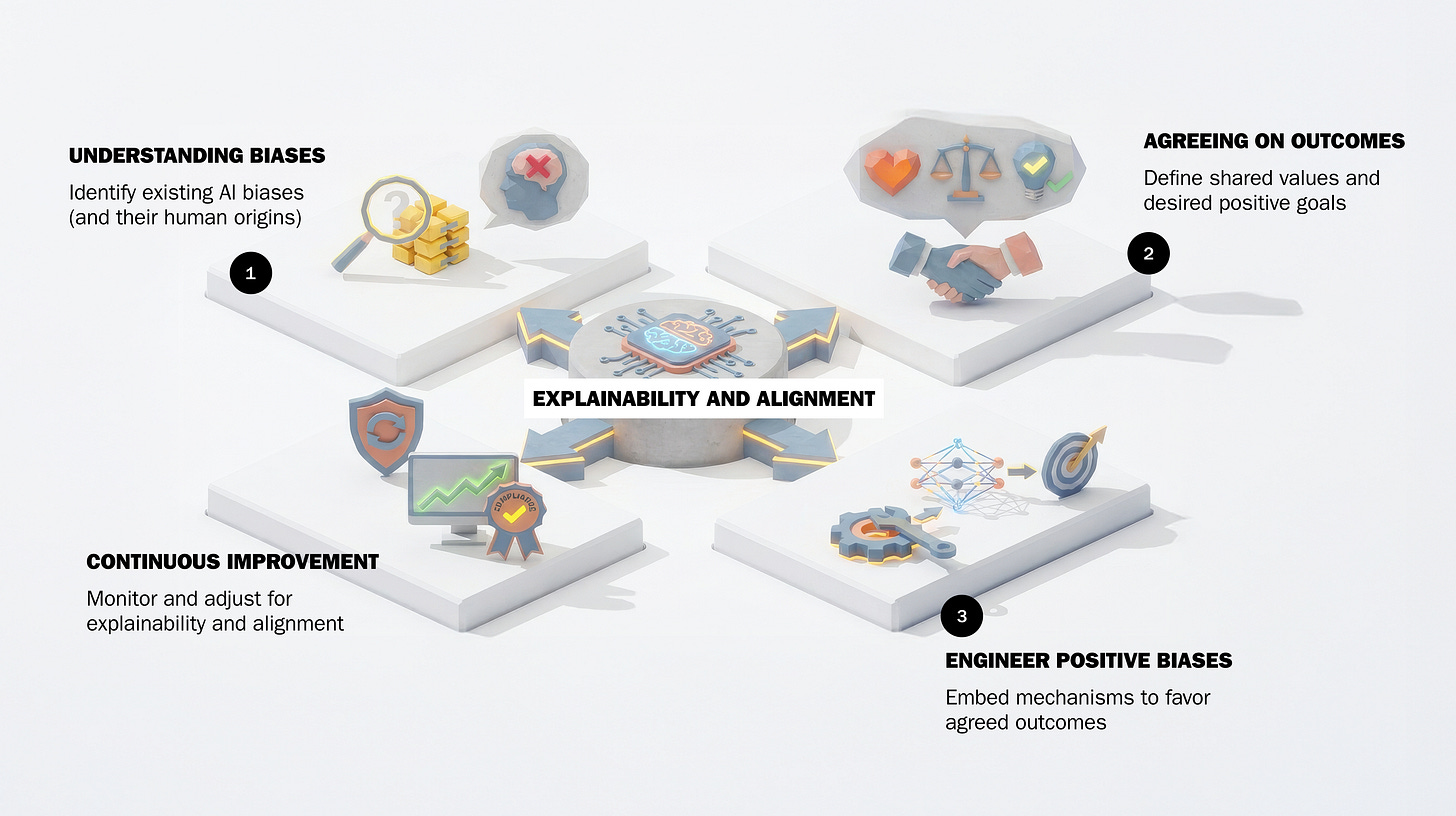

Have a strong “tendency, inclination, or prejudice toward” positive human outcomes. This is the Alignment Problem.

Share all of the information they considered (and how they weighted that information) when arriving at a decision. That’s the Explainability Problem.

Quickly, on alignment: alignment is the work that ensures AI models are focused on human interests/values, and can appreciate how their actions broadly affect those interests. AI companies spend billions on alignment, pushing machines until they act incorrectly, learning why they did, and using these insights to further align models with our desired biases and outcomes. (Last month Anthropic explained the clever method they used to learn how a model was reward hacking).

One of the major challenges in alignment is human: the same minds (ours) that argue and fight in the physical world (and are guilty of ills like racism, sexism, and inequity) will need to do the hard work of agreeing on what positive biases we want. With different value systems spread across the globe and societies, it will be difficult (if not impossible) to agree which ones should be encoded in AI; I call this the North Star Problem.

More likely than not, there will never be a single alignment solution. Instead, we will build standards model developers must adhere to, and governing bodies to hold them accountable when they manufacture misaligned models.

That brings us back to explainability.

Explainability is the process of unpacking the models’ bias in decision-making and reasoning by understanding what data they used, what tradeoffs they made, and where uncertainty entered the process. This is much easier to do with machines than humans because we can see the data stored in a machine (and machines don’t have ego or shame).

A common way to do this is to ask a model to “show its work” by breaking down a decision into many small steps and explaining the reasoning behind each one.

Explainability matters for three reasons:

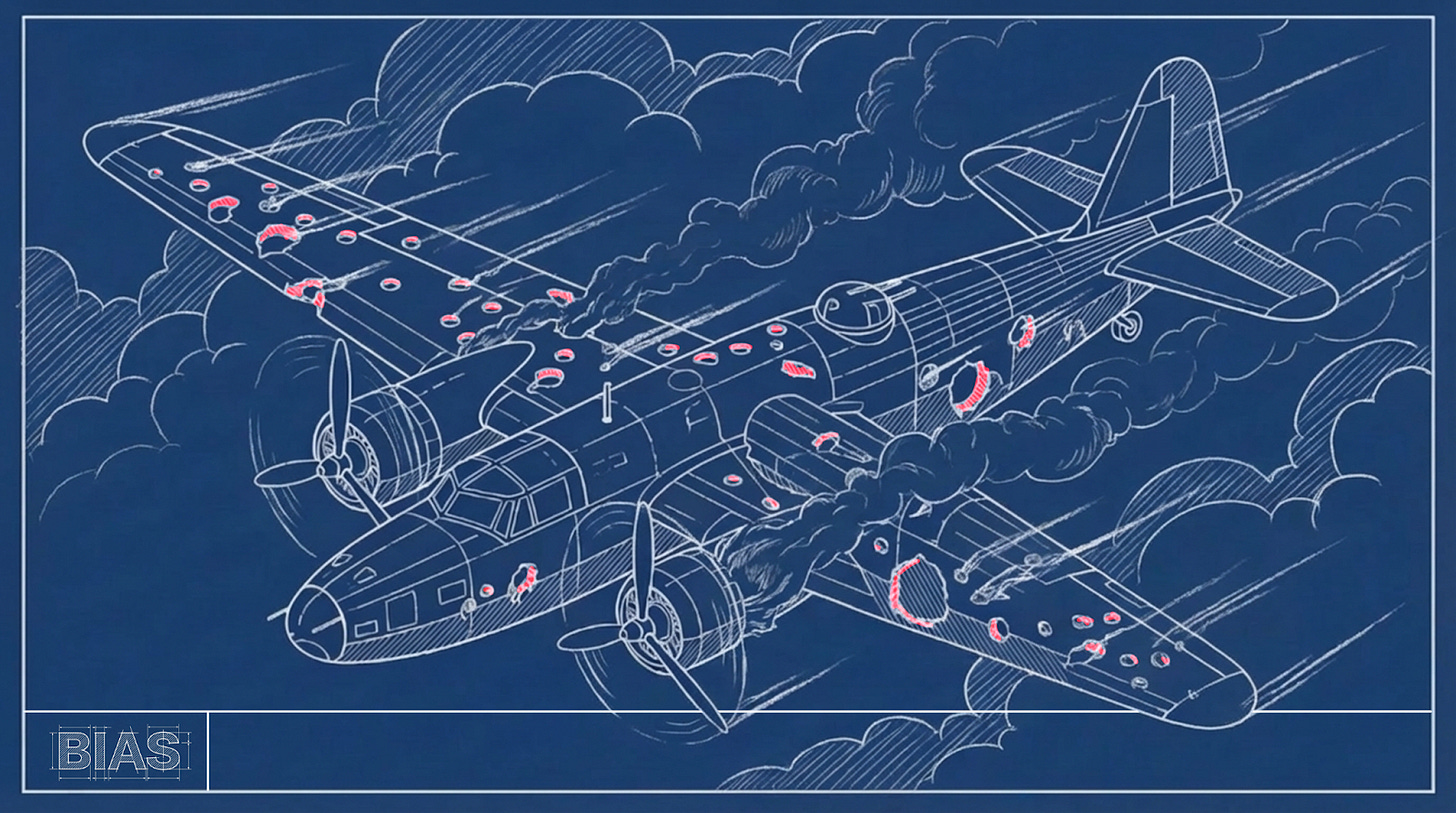

It reveals the biases already in the system, including those we did not intend.

It allows systems to be re-engineered toward better outcomes.

It builds trust based on understanding — not blind faith.

When machines explain themselves, they give us something human systems rarely do: legibility.

This advantage that can allow us to make opaque, human-centered decision-making architectures transparent; imagine admissions decisions, loan approvals, or court judgments that don’t end in “because I said so.” Systems that don’t just aim to be fair, but feel (and are) fair because their reasoning can be examined, challenged, and improved.

The work is not perfect — some AI biases will remain difficult to trace, just as they are in human minds. But success doesn’t require total understanding, only that artificial reasoning be easier to see and understand than human reasoning.

If we demand explicability, we can use AI bias to confront human flaws rather than amplify them — and build systems that are more accountable, more just, and ultimately more humane than the ones they replace.

Visit zackkass.com to learn more about Zack and get in touch.

In the world of electronic components, which is where you came into my orbit at a conference, transistors are biased with either a positive or negative electrical charge to establish a stable operating point. I read this piece with the understanding that bias is both positive and negative, but with a strong bias to believe that those whom stand to benefit the most from AI are biased to build AI tools biased to maintain the status quo. A source I am biased to trust on this topic is social scientist Christian Ortiz, Forbes article here: https://www.forbes.com/sites/janicegassam/2025/09/26/big-tech-ignored-bias-in-ai---justice-ai-gpt-says-it-solved-it/

Zack, this connects directly to our earlier conversation on the rules of AI.

You nailed the first layer: make bias visible, and it becomes manageable.

I've been building the second layer: semantic guardrails that prevent reinterpretation once visibility happens.

It's called ClarityOS. And your explainability thesis is why it works.

This essay should be required reading for everyone building it.

Would be worth a deeper conversation, curious if you see the same dynamics in alignment work.