The Tragedy of Unmetered Knowledge

Why we know too much; and the promise of unmetered intelligence

AI has already had some bizarre downstream cultural consequences. The average “corporate influencer” now has a fiduciary obligation to bill themselves as an AI expert — they’re often rewriting their past to do so — and *everyone* has the tools to “sound” smart by filling their newsletters and social media posts with big (meaningless) words. Syllable count has replaced concept quality as a means of communicating value. Exchanging ideas has become a game of word vomit performance art.

The result is AI slop (often about AI slop).

The worst part: algorithms are rewarding this editorial potpourri, elevating “experts” who trade on “smart-sounding” slop, publishing tens of thousands of words that somehow say nothing of real substance, and still attract enormous audiences. It exacerbates the entire problem. I don’t want to read it — I genuinely hate it; and I think most people do, too — and we certainly don’t want this trash shaping the zeitgeist for a few reasons:

Cultural malaise and “copy-pasta” aren’t good for the soul — McMansions don’t produce beautiful neighborhoods, etc.

Important ideas get ignored in favor of whatever drives attention — likes, views, impression.

And most importantly: polished-but-empty language conditions us to disregard what words actually mean.

Normalizing imprecise language is making (a lot of important) conversations about complex topics (like AI) overly simplistic and sloppy — and I see it as my job/purpose to bring nuance/precision to some of these issues.

As it relates to this blog post, a particularly glaring example of this is the indifference with which most people use the terms “knowledge” and “intelligence.”

Knowledge vs. Intelligence

Knowledge is acquired and stored information. It is all the facts, data, skills, experiences, know-how, and patterns we accumulate. Whether in humans or machines, it does not act on its own. It is an asset, a resource.

Intelligence is the capacity to interpret, transform, and extend knowledge — to glean meaning. Intelligence allows us to reason, learn, adapt, abstract, and make new connections. It is the tool we use to answer questions, solve problems, and seek deeper and broader knowledge.

Knowledge is raw power. Intelligence is the ability to use that power to do work.

Confusing the two causes people to misunderstand the scope/consequences of the internet (unmetered knowledge) and AI at scale (unmetered intelligence).

To realize the full potential of unmetered intelligence — limitless cognitive capacity delivered by AI at near-zero cost — we need to understand the difference between knowledge and intelligence, and how dramatically AI is going to change our relationship with both.

The Evolution of Knowledge

For most of human history, knowledge was scarce and inaccessible. In the 1700s, even Harvard’s library held only a modest 3,500 volumes. By the 1800s, thanks to the continued spread of Gutenberg’s printing press, an individual may have owned a few books and, if they were lucky, had access to a private church or society library.

By the 1900s, the explosion of public libraries in America expanded access to around 3,500 public libraries with tens of thousands of books in each. By the latter half of the century, it was not uncommon for even medium-sized libraries to have over 100,000 volumes, while Harvard’s ballooned to over 10 million.

This linear growth in access coincided with technological and societal advancements, but it pales in comparison to the logarithmic explosion of access created by the arrival of the internet.

In a single generation, we went from gatekept and geographically bound information to a world where almost every fact and framework is just one search away. (And that, folks, is why we call it the information age.)

By the start of 2025, the internet had an estimated 3.98 billion pages. Wikipedia has 64 million pages in English, and hundreds of millions of data files. Google Books hosts over 40 million books in over 500 languages, and the Directory of Open Access Journals has more than 22,000 open access journals and nearly 12 million research articles.

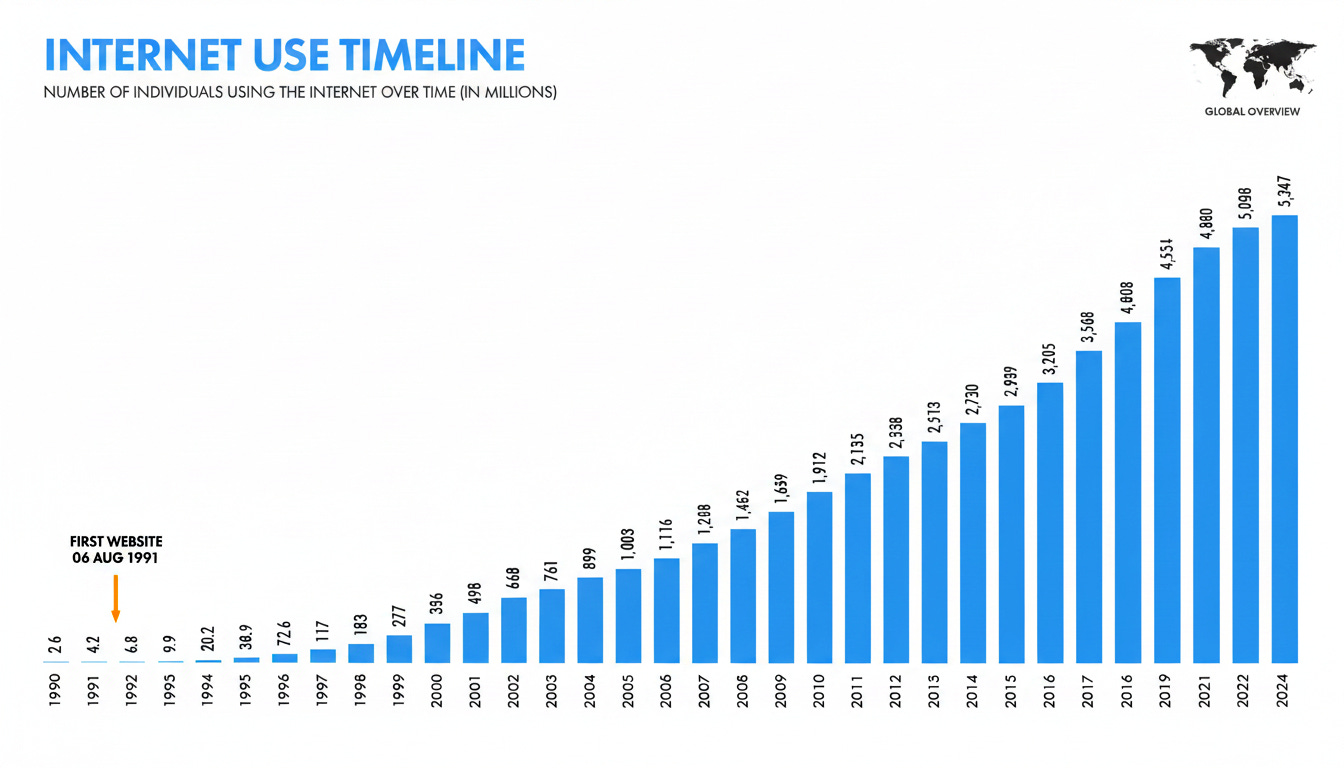

Across the planet, 5.35 billion people use the internet to access knowledge; that’s roughly 66% of all humans on Earth. In America the percentage jumps to 95%. Google handles 5 trillion searches a year. Online courses have boomed, with Coursera alone listing more than 142 million users. Even YouTube, for all its cat videos and MrBeast challenges, sees 70–86% of visitors using it to “learn new things.”

Humans today have more information at our fingertips than the greatest minds of history, Galileo, Newton, or even Einstein, could have ever hoped for. The tragedy is that it arrived before our human operating systems had a chance to keep up.

We are trying to process unmetered knowledge — frictionless, instantaneous access to the sum total of the world’s information — with brains only a few evolutionary steps from apes. We are filled to the brim, overflowing with knowledge, and it haunts us.

This tragedy plays out in two distinct ways. First, we are more aware of the goings-on in the world than any one of us reasonably should be. Any seven-year-old has access to the Darfur genocide, news reports of every single local murder, and the emotional devastation of losing a partner in Letter to Yi Ŭngt’ae from 1586 (”We’ll be together until our hair turns gray, then die together, so how could you go and leave without me?”).

There is value in knowing, but we are navigating a RAG marketplace with GPT-2 minds. Our brains run at human speeds, and are being served knowledge at machine pace. We are telling everyone, everything. We feel suffering at global scales. We cannot provide context. We can’t efficiently switch between topics. We can’t take a step back and see that, in totality, life on Earth continues to get better.

Second, we are not capable of mining the value of our knowledge for scientific discovery and progress. It is not unreasonable to think that somewhere across these pages, buried in millions of cells of data, we have the essential knowledge to solve cancer, fusion energy, or deep space travel.

We are buried in riches of data, and a Google search is not enough to dig us out. Unmetered intelligence is.

The Boom of Intelligence

In much the same way that the internet changed our relationship to knowledge, AI is scaling our access to intelligence toward unmetered intelligence.

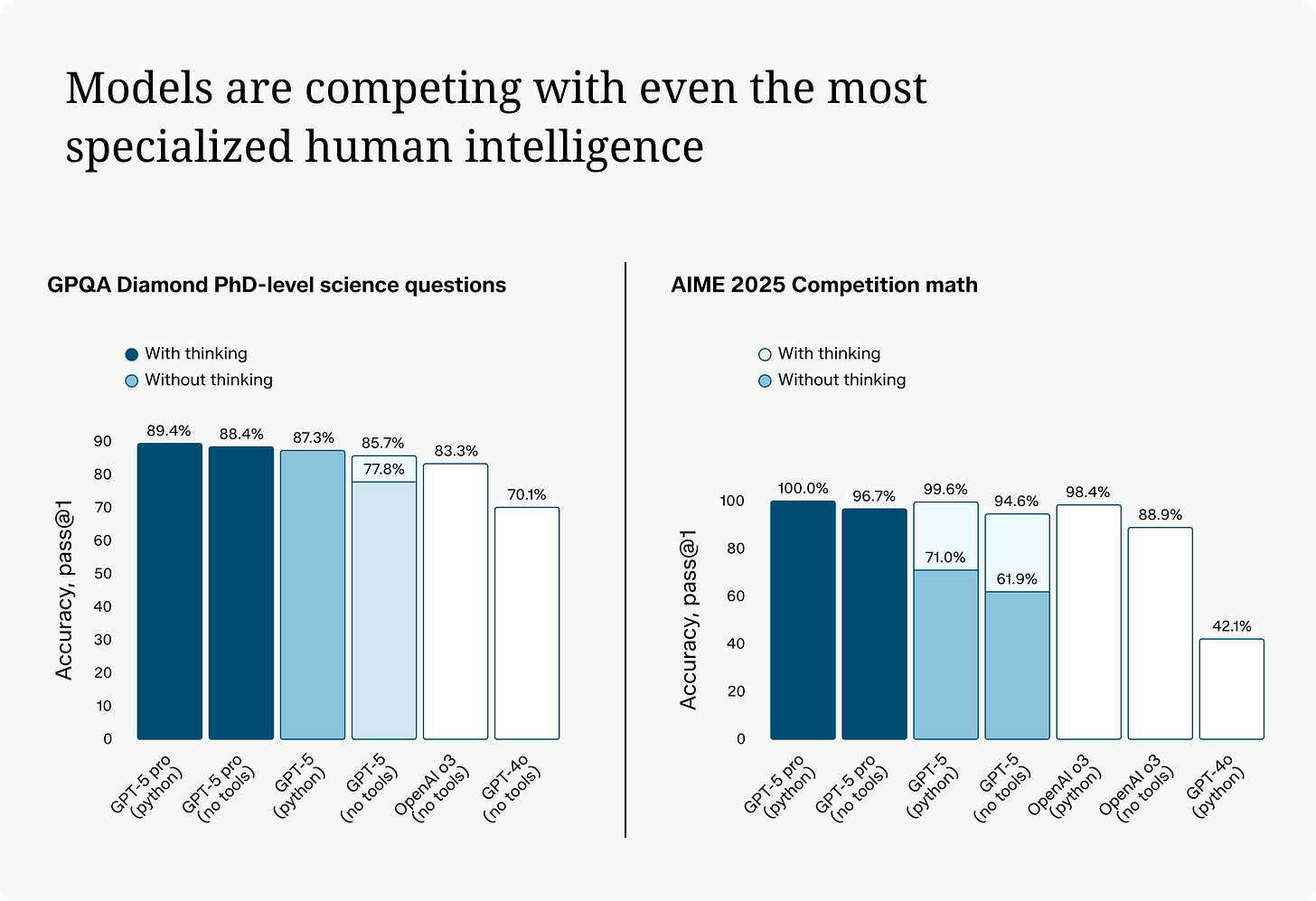

First, models are already reaching human-level intelligence. By 2023, ChatGPT-4 showed “human-level performance” on professional and academic exams, including scoring near the top 10% of test-takers on a simulated bar exam. GPT-5 scored 94.6% on the 2025 American Invitational Mathematics Examination, a test of complex math and problem-solving questions; the median human competitor scored 27–40%.

In 2024, Gemini Ultra became the first model to beat the average human score on the Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU) (89.8% vs. 90.04%), the go-to reasoning benchmark with graduate-level tasks from 57 topics including law, ethics, and history.

In the AI Index 2025 report, the Stanford Institute for Human‑Centered Artificial Intelligence reported that intelligence is only accelerating. In a single year, model performance improved 18.8% on MMLU, as well as 48.9% on the Graduate-Level Google-Proof Q&A Benchmark (GPQA), another reasoning test. Models also improved an extraordinary 67.3% on SWE-bench, a benchmark that requires models to read live GitHub projects and generate effective patches.

These benchmarks require deep reasoning and manipulating knowledge; outcomes that don’t come from a search function or scanning databases.

Models are improving their capabilities so rapidly that they are outpacing our ability to create benchmarks to test them. The frontier is being pushed not by expanding what AI knows, but by expanding how well it can think.

Second, and what makes me most excited, AI is creating intelligence at scales far beyond human capacity.

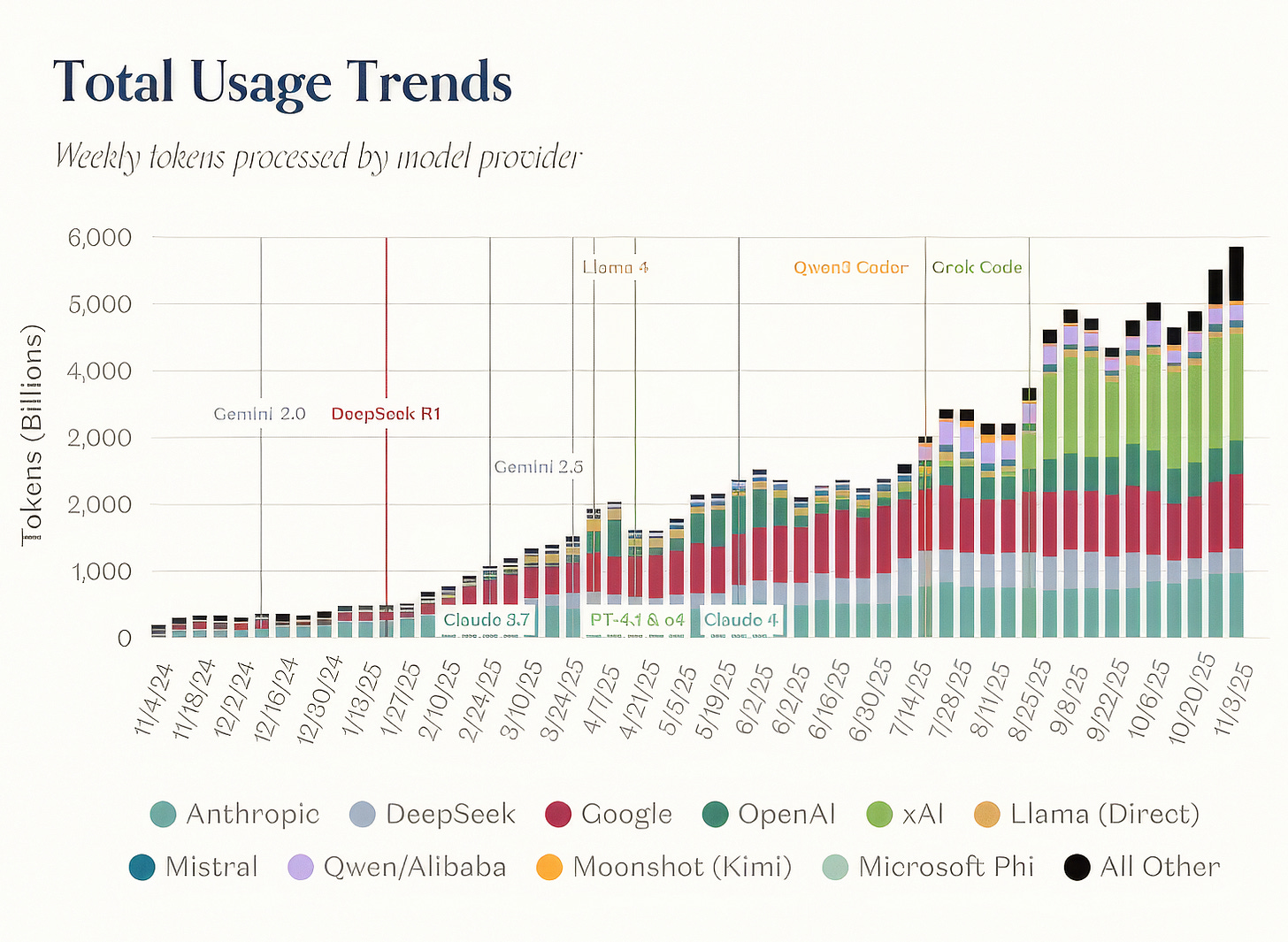

In September 2025, OpenRouter reported that ChatGPT generated 78.3 billion tokens in a single day. Think of a token as the basic ‘currency’ of language models — a tiny chunk of text (like a short word or piece of a longer word) that the model reasons over.

One token is about four characters, and 100 tokens is about 75 words. If an exceptionally fast human read 300 words a minute (the average adult can read about 238), we could expect them to process about 400 tokens a minute, and 576,000 tokens a day.

It would take that unsleeping, undying human 370 years of nonstop reading to match the cognitive work of ChatGPT from a single day. And as models improve and hardware becomes more efficient, available AI intelligence expands.

Unmetered intelligence addresses both tragedies of unmetered knowledge. First, it gives us our first meaningful tool to fight against the wave of knowledge that has overwhelmed us. AI can act as a membrane, synthesizing immense quantities of knowledge and only letting the necessary takeaways and context through (for example, GPT-5.1 provided a version of this blog for 12-year-olds and a version of this blog for 7-year-olds, but people of any age can use these tools to parse knowledge more effectively).

Second, it can add cognitive power to fields long limited by scarce human expertise — oncology, astronomy, nuclear physics, and more — to process existing knowledge toward new insights and discoveries.

The biggest impact of AI will come not from it being more intelligent than us (though in some arenas it already is, and in many others I think it will be soon), but rather from having more intelligence than us.

Intelligence in Action

After more than 50 years of ingenuity, rigorous science, and specialized human intelligence, the Protein Data Bank — a public, global database of protein structures — had identified about 190,000 unique protein structures.

In 2022, Google DeepMind launched the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database to do much the same work. In just three years, the open-source project used AI to predict over 200 million protein structures.

AI used the same knowledge available to the human scientists, but applied intelligence at scales large enough to solve the problem.

Perhaps all of the scientists in the world, with unlimited time, could have found each of these protein structures (I doubt it), but it would have taken generations and perhaps the total focus of humanity.

190,000 in 50 years vs. 200,000,000 in 3 years. The work earned the team behind the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database a Nobel Prize.

The Shift

The scope of human knowledge has long been confined to the answers of “definite problems.” How far away is the Sun? How large is the Earth? What are molecules made of? How can we improve crop efficiency?

But unmetered intelligence gives me hope that we will soon have enough cognitive capacity to aim for even larger questions. Questions that human intelligence could never comprehend, “indefinite problems.”

What is our purpose? What does the fourth dimension look like? How might alien life forms exist beyond our anthropomorphized imaginations?

There is a clear divide between intelligence and knowledge, but AI is increasing our access to, and the fruits of, both.

Visit zackkass.com to learn more about Zack and get in touch.

Thanks for the insightful article!! I really like your take on knowledge and intelligence being the tool to harness knowledge. Here's a thought I came up with while reading the part about AI solving problems/ discovering new solutions: Does intelligence come with creativity (creative problem solving) as well?

Well said, Zack. It makes sense that so many people feel overloaded. We’re moving through the world as curators of infinite inputs instead of experiencers of a single life, and our brains are struggling to keep up.