How to Raise a Successful Child

Or, The New Determinant of Achievement

Intellectual decline, especially with the arrival of AI, has been a major topic of concern lately; 61% of parents think greater AI use will harm students’ critical thinking, 55% of high schoolers agree.

I’ve written and talked about this issue quite a bit. Some of you have heard me discuss my theory of “idiocracy.” It describes the state an individual reaches when they decide that critical thinking is inconsequential to survival, and stop engaging in it.

Are We Getting Dumber?

When I talk about idiocracy, it’s often met with a chorus of disheartened nods. Most parents I speak to are worried about the general population getting dumber. This concern is certainly not without merit.

The NAEP 2024 (America’s education report card) shows only 28% of eighth graders are proficient in math, down 5% since 2019, and only 30% are proficient in reading, down 2% from 2019 and 5% from 2017. In low- and middle-income countries 70% of ten-year-olds are unable to read a simple text with comprehension, ballooning from 57% in 2015. The decline can be seen physically as well, 77% of pre-k to third grade teachers say students have more difficulty using scissors, crayons, pencils and pens than five years ago; early exposure to screentime is associated with fine-motor delay. Fewer kids can swim and ride a bike, per capita, than 20 years ago. All told, GenZ and GenAlpha, on average, appear to be the first generations in many to not be smarter than the prior—on average.

First, I should say: it’s pretty clear this condition predates AI. ChatGPT serves as a convenient scapegoat for the undoing of 20 years of education progress in literacy, but the evidence suggests we began this decline during the COVID lockdown (coinciding with the erosion of in-person education and a dramatic rise in screen time among children).

Second, it’s not limited to young people. In 2023, 28% of US adults were low performing in literacy, an increase of 9% from 2017, and 34% were low performing in numeracy, an increase of 5% from 2017. More and more adults are choosing to “switch off,” adult internet users around the world average 6 hours and 38 minutes online each day, with 31% of American adult social media users self-reporting daily doom scrolling. We now live in a world where is is possible to stare at your device for 16 hours a day, order DoorDash for every meal, and effectively turn off your brain.

But…buried in this data (because good news doesn’t sell ads) is a far more nuanced and promising story. While most parents I meet are worried about other kids, they often regard their child as much smarter than they were, at that age; and the data suggest that it’s not just their pride speaking.

The Rising Ceiling

While the average student appears to be in a recent decline, many are doing better than ever before.

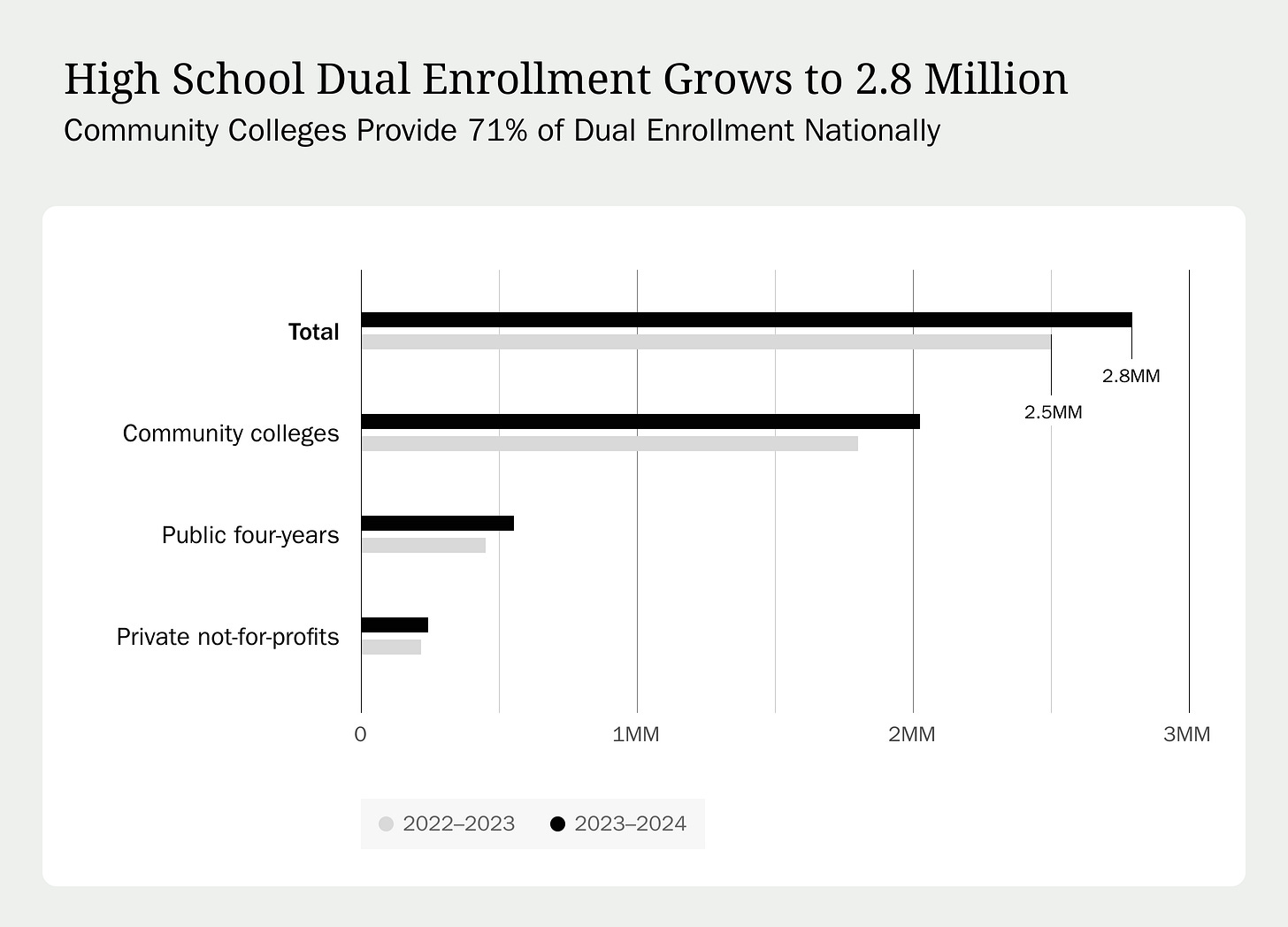

More than 2.8 million US high schoolers are taking college level courses, (fig. 1) and the number has grown more than 10% year-over-year. 35.7% of 2024 public-school grads took an AP exam, up nearly 3% from 2014. Students are earning the State Seal of Biliteracy at increasing rates, with double digits gains in some areas, including a 29% growth in New York City. Around the world, more than 96,000 students are enrolled in the IB Diploma Programme, an increase of more than 5% between 2023 and 2024.

Moreover, this performance cuts across socio-economic, gender, and geographic demographics. More than a quarter of AP exam takers in 2025 were low-income students; female enrollment in AP Computer Science is up 81% since 2017; IB programs are expanding in Ghana, Botswana, Togo, Peru, and beyond.

Young people are looking for opportunities to push and test themselves outside the classroom as well. Around the world, participation in FIRST robotics, a “sport-for-the-mind” robotics program, reached more than 785,000 students. Regeneron ISEF 2024, the world’s largest pre-college STEM competition (think: a super science fair) hosted 1,699 finalists from 67 countries and regions. 24% of 18–24-year-olds are actively starting or running a business.

Success, at an expert level, is arriving earlier and often outclassing the establishment.

A 17-year-old from Spain, won the 2025 Shigeru Kawai International Piano Competition against a field of adults.

An Argentinian 11-year-old, became the youngest player ever to surpass a 2500 FIDE rating (the international measure of chess strength).

A 17-year-old student in the UK used AI to remap textbook diagrams for color-blind learners, achieving 99.7% accuracy and expanding access to learning aids.

An 18-year-old trained an AI model on NASA data, uncovering ~1.5 million previously unknown astronomical objects.

A Florida high-school senior built an AI system to diagnose dementia with one brain scan.

An eighth grader created an AI tool to detect dyslexia.

A pair of 10-year-olds in Nigeria created an app to keep drivers awake behind the wheel.

And the markets are responding accordingly to all of this prodigal success: OpenAI and Palantir (among others) no longer require college degrees for employment.

For the first time ever, education and exceptional achievement are not dependent on access to institutional resources and human experts. Technology has un-gated these pathways to personal development. Entire communities long left out of the mechanisms of upward mobility can finally see pathways to equal opportunity.

Amidst all of the doom and gloom, something very good is obviously happening: technology is expanding potential and opportunity, and giving each of us new control over our own levers of success.

Concern for our general educational well-being is warranted, but we should celebrate that centuries-old barriers to opportunity are crumbling, and new abilities to question, learn, and explore are growing in their place—all over the world.

The Intellectual K-Curve

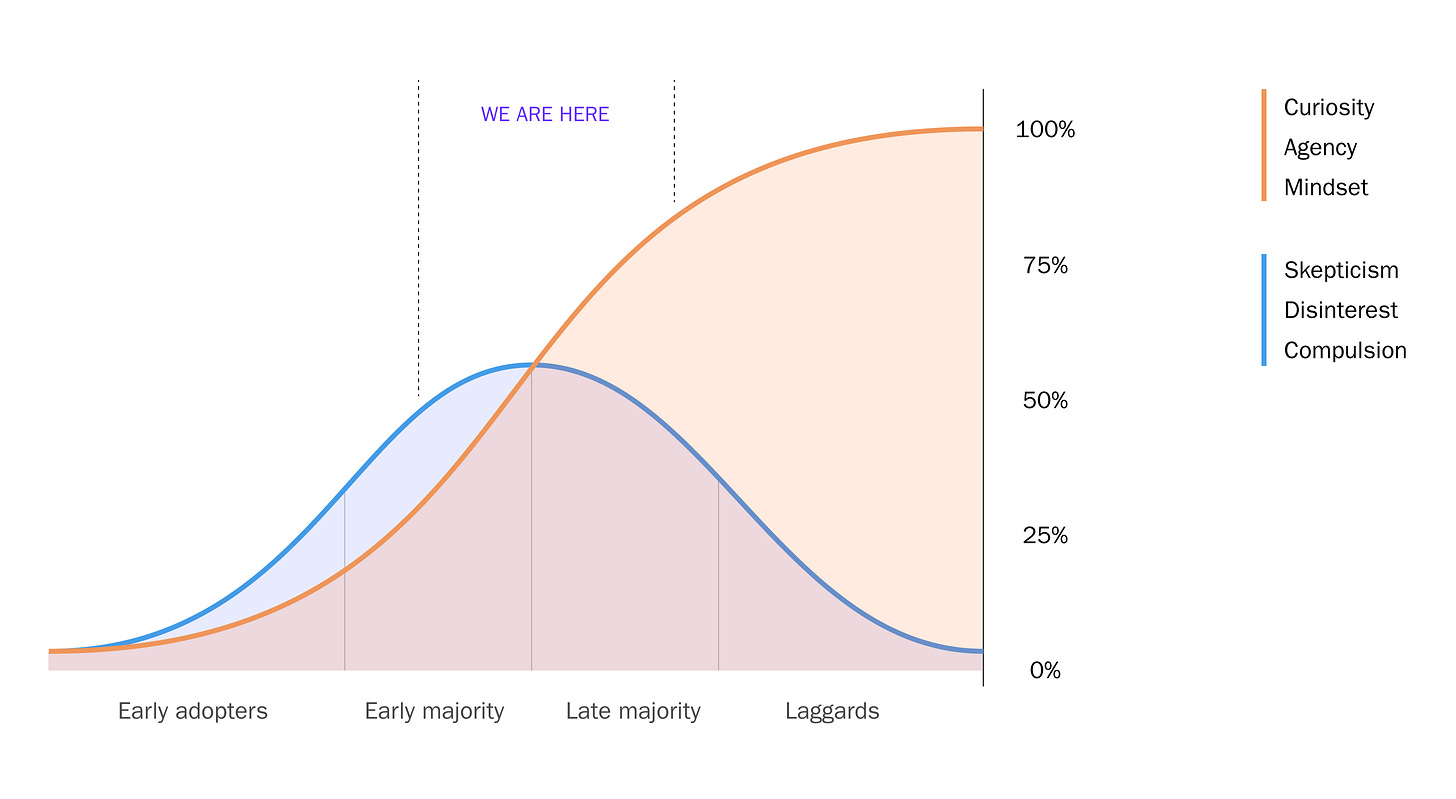

These two trends combine to form what I see as a new intellectual K-curve (fig. 2), the pronounced divide between those who are in the active pursuit of mental prosperity, and those who passively concede to intellectually rot.

The people who bend up the K-curve are leveraging technology to explore their interests and limits intellectually, creatively, and physically.

The people who bend down the K-curve are often succumbing to technology, passively opting out of intellectual exercise.

Most of those trending down have probably discovered that critical thinking is no longer of material importance to survival. Their opportunities and outlook tend to plummet along with their brain activity.

More and more, individual trajectories on the K-curve are not determined by circumstance, but by mindset.

We are observing, in real-time, that personal agency (or motivation) has become the primary corollary to personal achievement, outpacing even the juggernaut of socio-economic status.

Solving for Agency

Unlike other competitions, mental prosperity isn’t a zero-sum game: no one’s intellectual fulfillment requires anyone else’s failure. As a society, we should work, diligently, to help everyone bend up on the curve. To do so, we need to reward, above much else, agency.

Raising children to see technology as a means to accomplish more rather than a means to do less is one of the most noble things a society can pursue.

To do this, we must acknowledge a few things:

There is a cost to providing agency.

Our place on the K-curve is not absolute.

We can build systems to help more people bend upward.

Machine intelligence is rapidly approaching utility-scale affordability—what I call Unmetered Intelligence—yet what we do with it remains far from commoditized. Unmetered Intelligence does not mean universal brilliance, just as literacy does not mean everyone reads, or the internet means everyone does good research.

Developing this agency is going to be a deeply human pursuit that will require human intervention. Communities without access to guides, mentors, or parents with enough free time to nurture curiosity will inevitably fall behind.

But even those who are down are not necessarily out. The K-curve reflects motion; our places on it are not fixed. This creates opportunity for those on the downward trend to exercise their agency and rise—but it also means that all of us, across our lifetimes, must continuously pursue improvement: learning new tools, adapting methods, and choosing to grow.

So let’s build systems that help people reach the upward bend of the K-curve. Agency is not an innate ability determined at birth; it is a practice that can be taught and strengthened. We can cultivate it in ourselves and in young people. And to learn how, we should look to the kids already exercising it.

First, we need to create arenas to safely exercise agency. This is a key ingredient in many of the success stories above. The teen who discovered space objects did so inside the Regeneron Science Talent Search. The girls who created the driving safety app submitted it to the Technovation Global Summit. The MRI to diagnose dyslexia materialized at a county science fair.

Agency develops in places where failure is a pathway toward greater insights: opportunities like science fairs, Odyssey of the Mind, Lego League, math competitions. These are spaces for students to take risks, explore, develop, and learn outside of the strict architectures of academic achievement—pass/fail, grade point averages, class rankings—that reward completion more than pursuit. Young people need to feel safe to try, fail, iterate, and have their individual successes celebrated.

Second, we need to embrace interest as a pathway to agency. The student who built the color-blindness learning aid did so as a solution to his own struggles with color blindness. The student who designed a single-scan dementia screening had watched his grandfather suffer from the disease.

These young people achieved incredible things by pursuing the challenges and problems they cared about deeply; in doing so, they learned that their capabilities extended as far as their efforts, well beyond the measure of any grading rubric. This creates a sense of possibility, responsibility, and capability to pursue difficult things. Higher-order pursuits instill the confidence necessary to succeed in all tests, not just the one at the end of the school year.

The Pursuit

Ultimately, these strategies teach that what we do matters. Young students feel the consequences of their efforts, actions, and inactions, developing autonomy and ownership. The focus changes from reaching the floor to raising the ceiling—eagerly pursuing the upward bend of the K-curve.

These are humanist pursuits. I experienced them as a child when, even as a “bad” student (traditional schooling and I never quite fit), my parents encouraged my deep interests and gave me room to explore them. But I truly learned their value as a husband.

My wife, Adlee, is a first-grade Waldorf teacher. Whenever I visit her classroom, I watch her focus less on creating supreme test-takers and more on nurturing confidence, resilience, and agency. It’s inspiring to see children realize that they control their own time, attention, and effort—that things happen when they act. Adlee creates more capable humans who grow as they realize that accomplishments, like learning to tie their shoes, are within reach.

Through Adlee, I discovered a philosopher whose ideas have informed my understanding of agency, education, AI, and the child: Rudolf Steiner, founder of the Waldorf Schools. Not without his faults and prejudices, Steiner dedicated his life to the idea that education should cultivate the whole being, thinking, feeling, and willing. “Our highest endeavour,” he wrote 150 years ago, “must be to develop free human beings who are able of themselves to impart purpose and direction to their lives.”

AI has not changed this pursuit; it has merely expanded its reach.

Finally, a few thoughts for my readers who are not children (most of you), and may be thinking, “I wish I had known this when I was younger.” It is not too late. Agency isn’t age-gated. Follow the guidance of the youth: pour yourself into topics that interest you and delight in the process of becoming better than you were. Change your mind, eagerly. Then do it over and over again. Give yourself the space to fail, and the chance to grow along the way. Above all else, face the future optimistically, because now it is truly in your hands.

It might finally be reasonable to tell a smart, ambitious child (and yourself), “You can be whatever you want to be.”

Visit zackkass.com to learn more about Zack and get in touch

YES: Young people need to feel safe to try, fail, iterate, and have their individual successes celebrated.

Do you believe the path to agency can also be encouraged by faith and religion?