The Value of Cheap Failure

The New Economics of Rapid Experimentation

The MIT report (the one that found 95% of business AI pilots fail) made waves over the last month in business circles, and beyond. Journalists pointed to it as proof of a bubble, nervous executives promoted it as evidence that AI investment is massively wasteful, and practitioners seized on the moment to remind their bosses and peers how impressive their success is.

All of these interpretations (albeit reasonable) miss a major point that I’ve explained to execs for the last month.

95% failure doesn’t mean anything if we don’t consider what it costs to fail. And a 5% success rate doesn’t mean anything if we don’t consider what it pays to succeed.

Moreover, even MIT isn’t saying to not use AI at work — they’re selling courses for more than $20,000 aimed at executives to harness AI for business success.

Plainly, I’m not concerned with the 95% failure rate at all. In fact, I don’t think we are failing enough. Historically, the constraint on experimentation has always been cost — but that constraint is vanishing.

The Falling Cost of Failure

Adolphe Sax was obsessed with experimentation. In pursuit of a better sound, the 19th-century instrument maker constantly changed materials, key layouts, sizes, iterating over and over again, combining elements of woodwinds and brass until he found things he liked.

First, these experiments led him to improve the bass clarinet. Then, he built an entirely new family of instruments, the saxhorn, followed by the saxotromba, before finally creating the instrument that would put his name in the annals of brass, rock, and jazz: the saxophone.

Experimentation and iteration allowed Sax to explore his ideas, iterate on success, and create something new. It is also one of the fastest paths to find new ideas, solve unsolved problems, rethink past solutions, and discover the next problems to solve.

The thing about experimentation, though, is it can be prohibitively expensive. The Human Genome Project is estimated to have cost around $3 billion. The DOD and HHS obligated $13 billion to Operation Warp Speed, the effort to develop the COVID-19 vaccine. Adolphe Sax went bankrupt three times and had to sell his entire personal collection of instruments before dying of modest means.

When even success is expensive, the cost of failure, even the threat of failure, can stifle innovation. Though failure is a feature of experimentation, it has long been one of its largest constraints.

For many years, this has been the reality of AI. Training GPT-4 cost an estimated $80–100 million. Meta put the number for training Llama 3.1 at hundreds of millions of dollars. Goldman Sachs estimates that “The five highest-spending US hyperscale enterprises will have a combined $736 billion of capital expenditures in 2025 and 2026.”

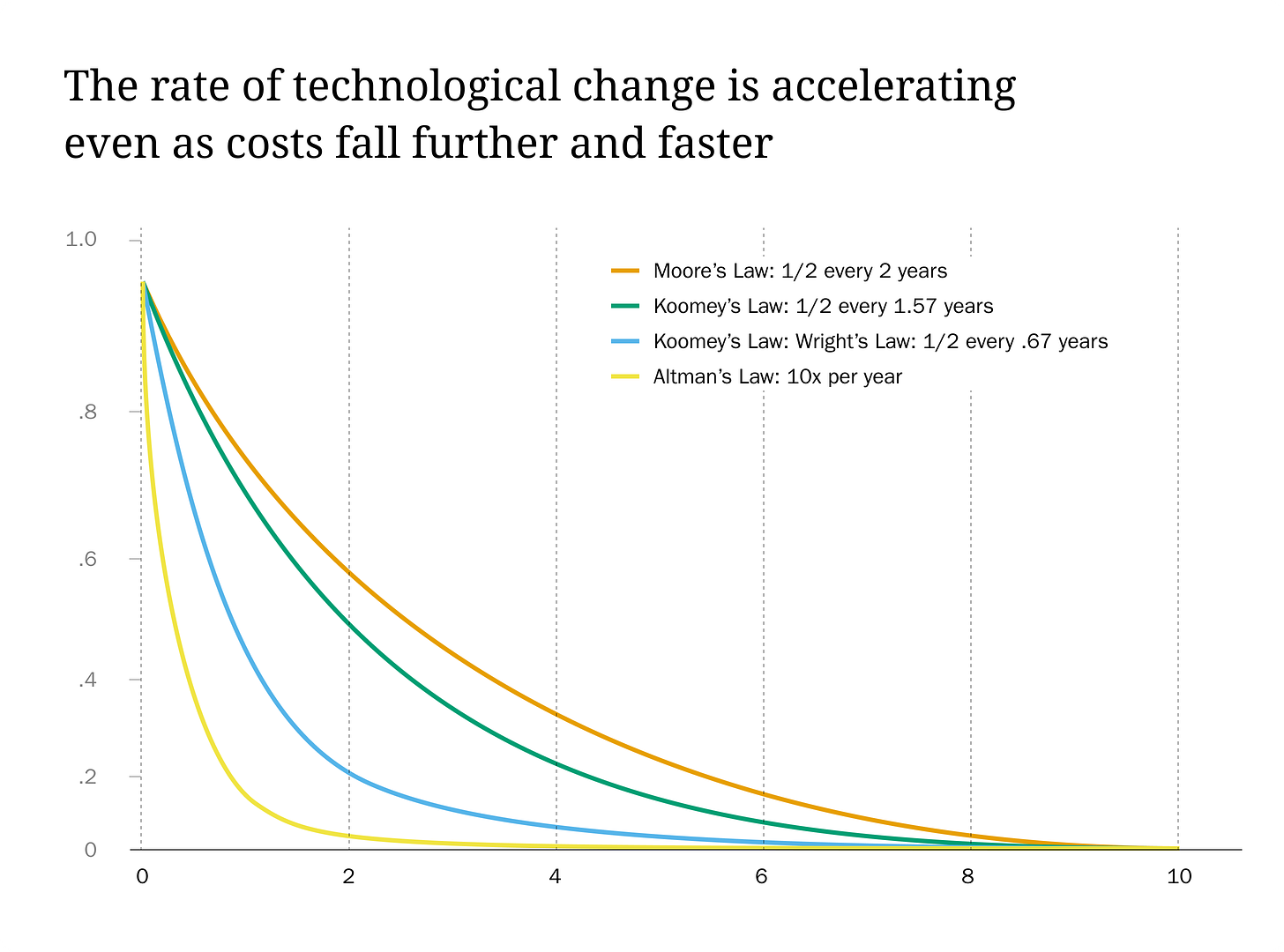

Crucially, though, while training a frontier model requires resources comparable to those of a small nation, the cost of using a model, the inference cost, has been in freefall. From 2023 to 2024, the price per token between GPT-4 and GPT-4o fell 150x. Sam Altman projected that “the cost to use a given level of AI falls about 10x every 12 months.”

Every year, it is getting cheaper to access the intelligence of AI. We are approaching Unmetered Intelligence, when intellectual capacity becomes as ordinary, accessible, and dependable as flipping a light switch. Compute, tooling, and algorithms are becoming as inexpensive to use as the electricity required to run them.

This means that any of us now have the capability to wield this intelligence. And when using a model is cheap, the cost of failure becomes cheap. The barrier to experimentation is disappearing. And while the experiments above were undertaken in specific fields, experimenting in AI can help us gain insights across industries and curiosities. This widens the scope of wonder, and the potential for discovery. We can do more, we can do it faster, and we can iterate at scale.

How Did It Get So Cheap?

To understand how exactly inference costs have gotten so low, and why they’ll continue to decline, it helps to get in the weeds a bit on the economics of compute.

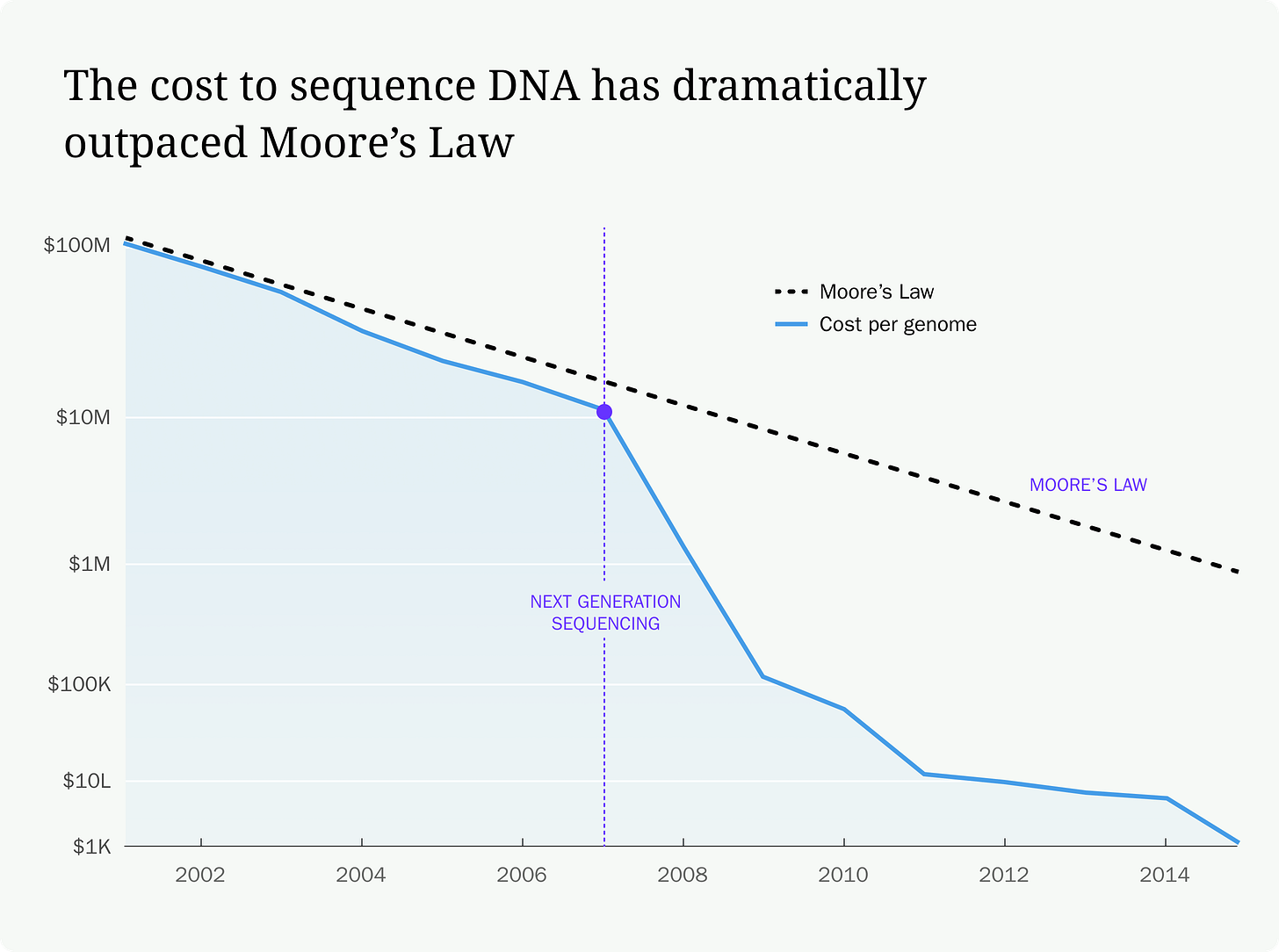

The largest set of reasons to point to is the same reason you pay less for gas in a Civic than a Silverado: efficiency. This efficiency plays out in a number of ways. We are getting more efficient at physically manufacturing compute power: the compute power that cost $18.7 million to build in 1984 cost $0.03 in 2017. This is known as Wright’s law. The computers themselves are also requiring less energy to do the same work; a recent report found that compute energy efficiency doubles every 2.29 years. This is Koomey’s law.

The AI algorithms themselves are also getting more efficient; in January 2025, DeepSeek released its DeepSeek-R1, which achieved performance comparable to other models while being 95–98% cheaper per task. And while demand for AI performance continues to increase, the efficiency of the data centers behind them continues to improve through scaling and improved infrastructure.

Innovations and competition are also decreasing costs. Increasingly, models are batching requests so that GPUs spend less time idle waiting for requests, and, of course, normal market factors (competition) are causing costs of cloud compute to decline, offering more, and more cost-effective options to run models.

How to Experiment More: The r-Selected Species

With these cratering costs (which look like they’ll continue to fall) the experiment tax is collapsing — when the cost of failure is low, the cost of many failures is only marginally more. That flips the calculus of exploration and failure: the downside is minimal, and the upside, especially at scale, can be tremendous. The advantage shifts to those who convert that deflation into more shots, sooner, with stronger learning loops.

This is going to require change. We don’t like failure, and many of us have a hard time learning from it (at least in the short term). Success requires a mindset shift. It is time to channel our inner r-selected species.

You might recognize the term from high school biology: r/K selection theory. It separates species into two groups: r-selected and K-selected.

Humans, biologically, are a K-selected species. Our strategy to raise our young successfully, so that they can go on to raise their own young, is to invest in them heavily. We can only have a few offspring (no litters), they take longer to reach maturity, and they need heavy parental care. If it goes well, our offspring are larger, they live longer, and they have a higher chance of survival. K-selected species thrive in stable environments. We’re not the only species that does it, so too do elephants, whales, and emperor penguins. It’s a quality over quantity choice.

r-selected species take a different route. Theirs could be described as quantity over quality. They have many offspring, they’re often smaller, they mature early and require little parental care to go off on their own. Many will die, but many will also survive. These aren’t really species that we often laud (I was going to say lionize, but — K-selected species), they’re the ones that thrive in instability: mice, fruitflies, bacteria.

To be successful in the future, you must run experiments like fruit flies: cheap, fast, and plentiful. Experiments can spread far, spread fast, investigate any opportunity, and swarm on success; building on one another in wave after wave of experimentation.

The Individual and Company Swarm

For companies, a culture of experimentation should not be considered aspirational, it needs to be treated as forward-compatible infrastructure. It is not enough to run quarterly “innovation sprints.” Companies must become perpetual idea and implementation factories: experiment with copilots in familiar apps, AI assistants, calendar managers, email triage, client outreach, customer service, and look for any other advantage (or more stars like the student I wrote about last week).

Rather than going for K-selected “big bets,” capital-intensive gambles that require extensive compute and human brain power, try micro-bets, and try a lot of them. Hypotheses are no longer budget decisions, they’re keystrokes. Your goal isn’t one big win; it’s a steady drumbeat of small, cheap trials that compound into advantage.

This isn’t only true of businesses though, each of us, personally and professionally, can experiment to achieve and ship more in our lives. Treat more questions, tasks, and ideas as opportunities for experiment: draft the memo, prototype the feature, spin up the side project, test ten versions, keep the ones that work and build on them.

Do this because it’s interesting, and do it because automating rote tasks and expanding your mind is a moral good. Find ways to do more and reclaim hours of your life. More and more I’m meeting people who tell me experimentation with AI has led them to building systems that allow more time for everything else. The more we explore with AI, the less we have to actively use it.

Quality ideas, care, and motivation will still matter, but we can direct them more efficiently by leveraging quantity and speed. Experimentation isn’t a detour from progress; it’s the shortest path to it.

Fail Effectively

As you experiment and embrace failure, make sure you do so while allowing yourself to succeed. Measurement is the difference between motion and progress: know exactly what you’re testing, and learn from the result — success or failure — so you can act. The goal isn’t to “win” every experiment; it’s to convert ambiguity into learning you can use.

Frequent failure can be emotionally expensive, so normalize it. Highlight what was ruled out as progress, and separate self-worth from hypothesis worth. Prepare for legacy resistance by creating time, space, and safety to fail toward progress without raising a red flag for higher-ups. And in high-risk domains — user impact, data sensitivity, regulatory exposure — don’t just experiment fast; experiment safely with human-in-the-loop checkpoints, reviews, and rollback plans. Speed where it’s safe, and safeguards where it’s not.

Build, Build, Build

As our capabilities continue to surge, and our needs and interfaces keep shifting, develop the muscle to reinvent frequently. Unmetered intelligence means that experimentation doesn’t end at financial ruin, and it doesn’t end at success; it’s a pathway for sustained progress. We have to keep walking it.

So my call to you is to experiment, and build. And do it frequently.

The only rational response is to try more, and the only real cost is in not failing enough.

Visit zackkass.com to learn more about Zack and get in touch

I love that Kass encourages us to experiment more because in the age of Unmetered Intelligence the only real cost is in not failing enough.

Love this, low cost of failure lowers risks and promotes more embracing of rapid testing.