The Adaptability Trap

There’s never been a better time to disagree. Part I of II

A few weeks ago, at LinkedIn’s AI in Work Day event, chief economist Karin Kimbrough stood before the crowd and confidently declared that in a changing world, “adaptability is the new currency.”

As definitive statements go, it’s as banal as it is aspirational.

Adaptability has always been a virtue, and it is one of the critical (and unique) features of Homo sapiens’ evolution. But adaptability carries a hidden pitfall, especially during times of radical change.

When the drive to adapt overwhelms everything else, it can hollow out conviction. History has watched spineless leaders twist themselves into whatever shape they think the moment calls for, forgetting that some tides are supposed to be resisted, and not all change merits adaptation.

We love to tell stories of companies that failed because they didn’t adapt — Blockbuster, Kodak, BlackBerry. But just as many have died from over-adapting. WeWork reinvented itself until no one knew what it was. Yahoo chased every trend until it stood for nothing. GE pivoted so hard it forgot what business it was in. Even Nokia, once the world’s most innovative handset maker, collapsed under the weight of too many changes.

These weren’t failures of imagination; they were failures of conviction.

This, to me, is the Adaptability Trap: when the instinct to survive or impress overwhelms the one to lead. Change becomes more appealing than core values, and purpose is lost in the shuffle.

What’s the Buzz on Adaptability?

“Adaptability” has become a catch-all strategy for an unnervingly unclear near-future for two reasons.

The first is that it’s aspirational and sells LinkedIn feel-goodery slop. It lets individuals feel like control is still in their hands; they just have to change enough! The second is that it allows leaders to feel like they are building an arsenal to solve any problem (and convince the powers above them that they are as well). If they just hire endlessly adaptable workers, the company will change to meet whatever the future brings. Problem solved.

Scale AI’s interim CEO Jason Droege recently told Business Insider, “The world’s changing, right? So you do need people that are adaptable.” In a late 2024 SAP corporate blog, the company stated that shifting skill demand in the workplace “underscores the need for adaptability as workers learn to stay relevant in an evolving job market.” They reinforced this position in early 2025 saying organizations can “create a people ecosystem centered on adaptability and growth.”

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics now includes “adaptability” in its Employment Projections skills taxonomy, formalizing it in skills frameworks. In the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2025, 67% of global employers labeled resilience/continuous learning — foundations of adaptability — as rising core skills, an increase of 17 percentage points since 2023, leading the report to single out “the critical role of adaptability.” These skills only lagged behind “analytical thinking” in skills rankings.

Adaptability is ascending for good reason. But I fear that — like the child who eagerly runs to the top of the snowy hill only to realize they forgot to bring their sled — our pursuit of adaptability is leading us to leave the most important things behind.

The Chameleon and the Shapeshifter

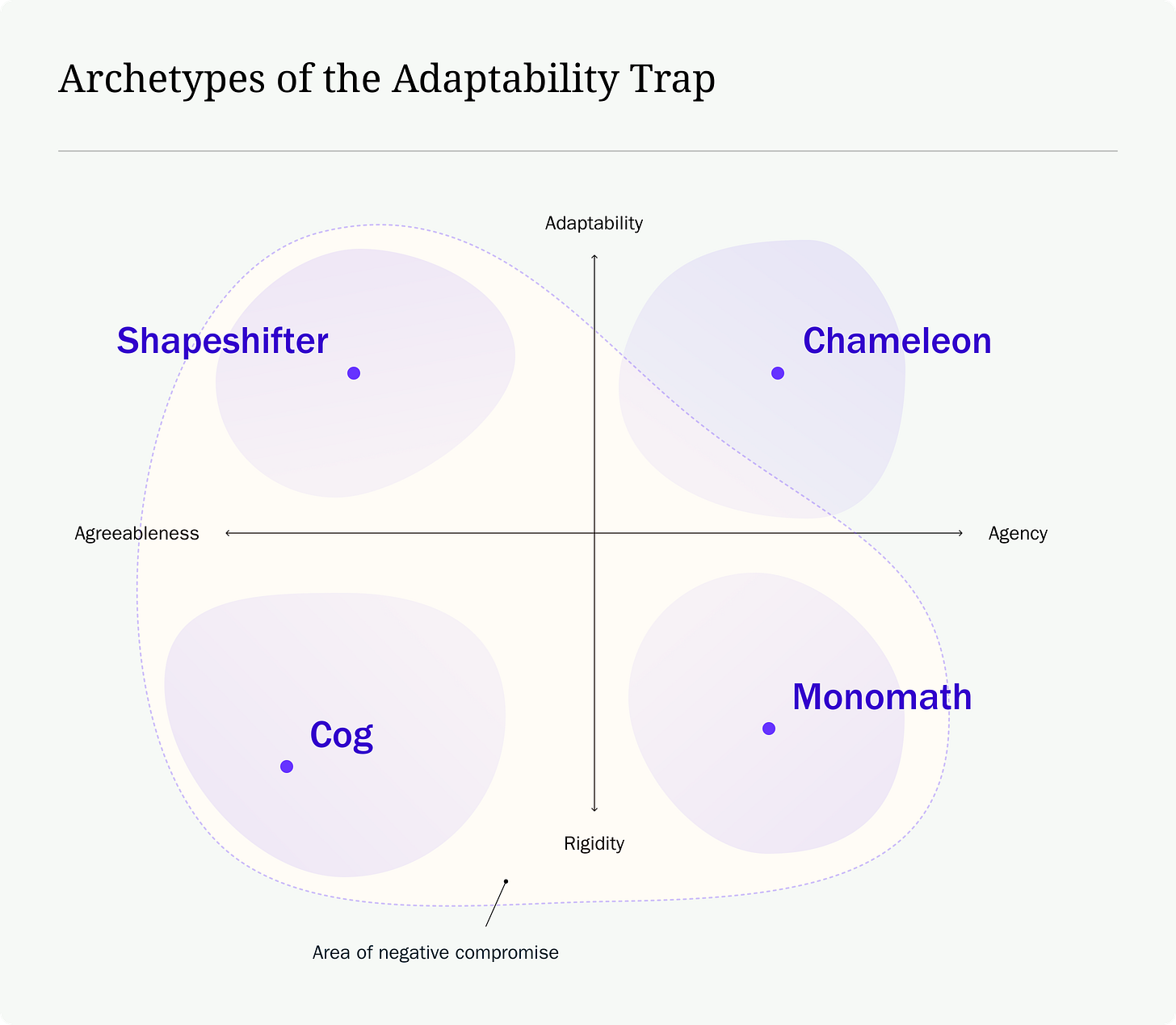

It’s a bit simplistic, but I think there are basically two archetypes of adaptation: the Chameleon and the Shapeshifter.

Chameleons can fit most anywhere while staying true to who they are. They shift tone, language, and behavior to match their surroundings, but their core beliefs remain intact. They read the room well, and know who they are when they leave it. They’re easy to get along with, but their adaptability has limits. The color changes; the creature doesn’t. In moderation, this kind of adaptability is a strength — it’s insight and empathy in motion. Plus, they’re fun to be around.

Shapeshifters, on the other hand, will abandon everything to try to become the “perfect” fit. They don’t just change behavior; they change form. Their flexibility is absolute — a full-body surrender to circumstance. Think of the man who, under the full moon, undergoes grotesque transformation into a werewolf. Nothing remains of the old self, no structures, no beliefs, no morals. The Shapeshifter forgoes the foundations of the last form in pursuit of the benefits of the next. They’ll say whatever gains approval, endorse whatever wins favor, and they mistake malleability for growth. They’re unnerving people to be around.

Both thrive in systems that value adaptability above all else — they’re masters of change. But when organizations reward the ability to contort and change more than the courage to stand firm, they start selecting for Shapeshifters — leaders who can survive any challenge or change, except the test of conviction.

The Cog and the Monomath

Though they may be falling out of favor, understanding the archetypes of rigidity, the Cog and the Monomath, can help us better understand the Chameleon, the Shapeshifter, and the Adaptability Trap.

Cogs do not adapt, and they do not stand up for themselves. These individuals simply do their job. Anything beyond function is beyond the purview of the Cog. Core values are inconsequential compared to the task they are assigned. Think of the ditch digger, they simply dig ditches.

The Monomath is rigid in their pursuit, and firm in their convictions. Their area is that of singular focus and deep expertise. Their core values, principles, and mission remain unchanged as they constantly work to refine their craft, to zoom in even further. Think of a 100-meter runner. They are focused on running, but they work to get faster.

Agency and Agreeableness

While these archetypes seem opposed, they snap into focus when we consider them across the axis of agency. As I recently wrote, agency is the common corollary to personal achievement.

Adaptability allows us to change; agency allows us to stand firm, to question, and to grow.

The Chameleon and the Monomath express agency. They preserve what is important to them and stand by their convictions while deepening expertise and abilities. How they go about pursuing the things that matter to them differs (adaptability vs. rigidity), but they share the power to do so. By leveraging agency, they move forward while holding their core values close.

Opposite agency is a trait that absolutely drives me wild: agreeableness. The Cog and the Shapeshifter are infinitely agreeable. They do not stand firm to any core beliefs or convictions. The rigid Cog has no core beliefs to hold on to. The adaptable Shapeshifter is willing to change any core belief in order to survive and impress.

Without guardrails — vision, mission, values — adaptability becomes moral drift. It reminds me of a passage from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

ALICE: Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?

CHESHIRE CAT: That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.

ALICE: I don’t much care where.

CHESHIRE CAT: Then it doesn’t matter which way you go.

When the destination is undefined — the purpose for the journey — any pivot feels justified, and change feels like progress.

The goal isn’t to eliminate adaptability but to anchor it. Be Chameleon enough to understand and adjust to the world around you, but not such a Shapeshifter that you lose yourself within it. Build environments where employees can express their own agency, while preserving the company mission and values. The challenge of leadership in an age of constant change is knowing what must evolve — and what must endure.

The Dangers of Infinite Adaptability

Within the Adaptability Trap, low-agency employees learn there is no reason to push back, and no vision to push for. This creates workplaces full of sycophants whose easiest path forward is to nod, agree, and react.

Employees “figure it out” rather than finding ways to “make it right.” A worker beaten down by a flawed internal system, a poor manager, or supply-chain inefficiency just deals with it. They don’t hold firm to company beliefs, challenge assumed outcomes, flag concerns to management, or warn of values drift.

Research shows that when people tailor how they present themselves to every situation, or “self-monitor,” they exhibit lower attitude‑behavior consistency. What they say is less likely to predict how they will act. When hiring for unlimited adaptability, employers risk getting flaky, unpredictable employees.

For individuals, the Adaptability Trap is a race to the (moral, financial, and vibe) bottom. It promises agency but actually strips people of it. Why would an employee flag an issue if they felt it would signal to their employer that they aren’t adaptable enough? Infinitely adaptable people become agreeable to anything and accountable for all of it. They will say yes to ever-expanding KPIs, absorb “just one more” project, forgo pride in work, pursue completion, and abandon the mission that may have attracted them to the organization in the first place. They will adopt all the tools, and get real value from none of them.

The dangers seep all the way into personal identity. Research suggests that constant personal adaptation can cause the image of yourself, the self-concept clarity (SCC), to become fuzzy. When we change for everything, we start to forget who we are. Low SCC predicts stress, depressive symptoms, lower self‑esteem, neuroticism, greater susceptibility to external cues, poorer self‑regulation, and poorer life satisfaction.

There’s Never Been a Better Time to Disagree

What frustrates me most about the current worship of adaptability is how misplaced it’s become. We keep telling people to bend, pivot, and adjust — but rarely to question. The irony is that there has never been a better time to express your agency, to hold your ground, to test assumptions, to challenge the direction of change.

For most of history, agreeing and adapting made sense. Your boss, your teacher, your elders did know more than you. They’d seen more of the world, faced more challenges, and had access to information you couldn’t dream of. Adaptability and agreeableness were survival.

But that’s no longer true. The monopoly on knowledge is gone. Anyone can access the world’s ideas, data, and expertise in seconds. If your boss makes a claim or a decision that feels wrong — or betrays the mission — you no longer have to nod in silence. You can test the logic, pull the evidence, and model the outcome yourself.

Adaptability without discernment is regression.

Adapt How, Not Why

Avoiding the Adaptability Trap, while staying relevant, requires exercising agency and conviction alongside adaptability. By preserving those things most important to their core — values, mission, vision — leaders and companies can lead while meeting the evolving demands of the outside world.

This is the promise of what I call Behavioral Adaptability — the capacity to alter one’s practices and habits in response to changing conditions, while maintaining one’s deeper principles. This creates stability through change, and builds a foundation that allows employees to question, learn, and grow.

There is a clear distinction here from the Adaptability Trap. The Adaptability Trap is a willingness to change everything, to be a Shapeshifter. Behavioral Adaptability is a willingness to change how you pursue what is most important to you, to be a Chameleon. Agency begets agency, and builds safe sandboxes for experimentation and progress.

Leaders and individuals need to determine when to adapt, where to push back, what to change, and what to never surrender. This is the way to proactively prepare for a changing future, without leaving yourself behind.

How to do so — is a topic for next week.

Visit zackkass.com to learn more about Zack and get in touch

I like how this captures why some pivots feel purposeful while others feel like moral drift. I'm keen to read Part 2 on how to decide when to adapt and when to hold firm.

Great piece - I have shared it with our senior leaders!