False Boundaries, Blowback, and the Return of the Real

Three Trends for 2026

Prophesizing any single event more than a year out is hard; accurately predicting further than that is a fool’s errand. As a result, bold predictions (especially those made loudly) are mostly just personality tests.

Even so, people often ask me what I think the future holds, and I’m inclined to provide an answer.

So here you go: I believe that unmetered intelligence — cognitive capacity at near-zero cost — will deliver a few trends in 2026:

Roger Bannister Moments — the exposure of false boundaries

Three Mile Island Moments — the reckoning of major downside events

A renewed hunger for, and investment in, the physical world

1. We Will See Multiple "Roger Bannister Moments”

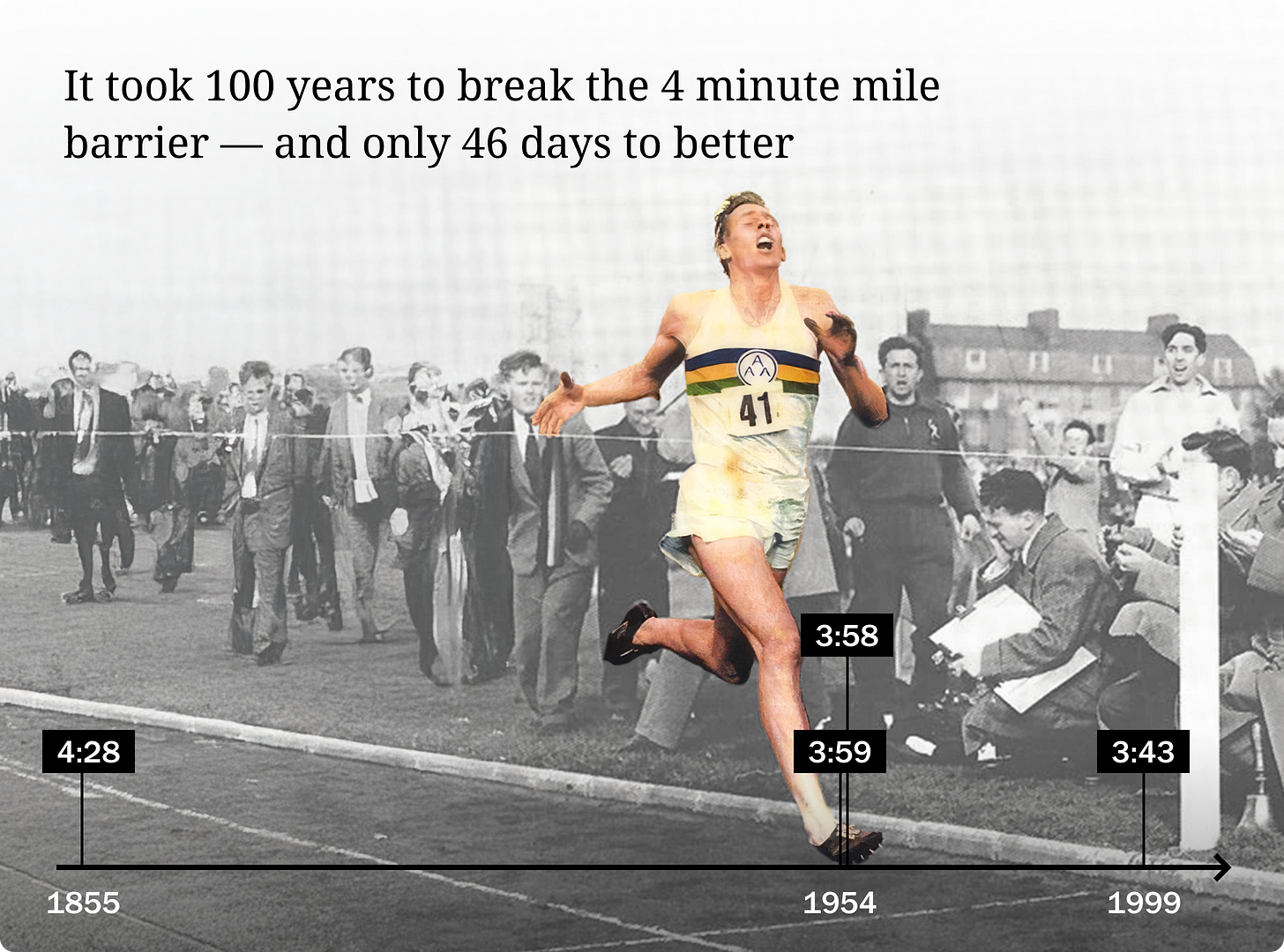

For centuries, physiologists believed that running a four-minute mile was physically impossible. They believed the human heart would explode, muscles would tear from the bones, and athletes would collapse as they pushed past their limits. Runners mostly believed this as well, adding a psychological boundary to the perceived physical one.

Then, on May 6, 1954, in Oxford, England, Roger Bannister ran the mile in 3:59.4.

Roger Bannister will forever be remembered as the man who revealed a false boundary. Even more impressive is the fact that his record stood for only 46 days. In less than two months, Australian John Landy broke Bannister’s record by a second and a half. Within three years, 16 men had run a four-minute mile. When Bannister proved that the physiological and psychological limits were false boundaries, he opened the floodgates.

Bannister’s accomplishment went beyond fitness, it exposed a deeper truth about human performance: belief changes what the body is willing to attempt.

Once a limit moves from impossible to done, effort reorganizes around the new ceiling. This pattern appears well beyond running. The placebo effect shows that expectation alone can measurably alter pain tolerance, endurance, and even physiological markers. The Pygmalion effect demonstrates that people perform better when more is expected of them. And decades of research on self-efficacy, led by Albert Bandura, show that individuals who believe success is attainable persist longer, tolerate discomfort better, and recover faster from failure. When belief updates, behavior follows. Progress, more often than we admit, is unlocked by the realization that the old limit was never real.

Recently, we’ve seen several false boundaries collapse. For decades, a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis (CF) meant a sharply shortened life; many patients didn’t survive past their teens. That understanding unraveled with the approval of a triple-drug therapy in 2019 — effective for roughly 90% of people with CF — and with additional therapies moving through laboratories in 2025. As a result, newborn life expectancy for CF patients has risen to levels approaching that of the general population. Human biology didn’t have to change — our ability to navigate it did.

AI and unmetered intelligence will produce similar “Bannister Moments” across industries by revealing many presumed limits as resource constraints, rather than physical constraints. These false boundaries tend to fall into three categories: soft boundaries, imposed by cost or time; social boundaries, reinforced by the collective belief of what “can’t be done”; and interface boundaries, where answers exist but are buried in complexity beyond human cognition.

AI is an aggressive solvent for all three — and we already have the evidence. Drug discovery once depended on years of trial, error, and luck. In 2025, researchers at MIT used AI to invert the process, screening 36 million compounds to identify candidates effective against drug-resistant bacteria. At NJIT, researchers applied AI to discover new porous battery materials, bypassing the physical bottleneck of testing millions of material combinations by hand. And at UNSW, machine learning reduced more than 8,000 potential green-ammonia experiments to just 28 high-probability targets — turning years of failure into weeks of focused validation.

The same dynamic plays out at the individual level; people carry their own false boundaries — beliefs about intelligence, creativity, leadership, or resilience — that feel permanent only because they’ve never been bested. But once an individual sees proof that things might not be as they seem, behavior changes: I can do this. Effort increases. Risk tolerance expands. Persistence follows. Psychologists describe this as self-efficacy; most people experience it as growth. It is the same mechanism that drives societal progress: beliefs update in response to evidence, and capacity expands as a result.

In 2026, we will start to recognize that some of our most stubborn limits — personal and collective — were never laws of physics, only limits of human bandwidth. As discovery shifts from lucky breakthroughs to reliable, AI-driven search, progress in longevity, clean energy, heavy industry, and personal agency will accelerate — and what once felt miraculous may start to feel… routine.

2. The Industry Faces a "Three Mile Island Moment”

Failures have already occurred during AI’s rapid expansion: hallucinated legal citations, automated systems reinforcing bias, deepfakes used for fraud, AI-enabled scams at scale, and opaque models embedded in consequential workflows without sufficient oversight. AI’s public perception has largely survived these incidents because their costs so far have been diffuse, reversible, or absorbed quietly.

The risk ahead is not the first failure. It is the first highly visible, emotionally resonant failure — one that is confusing, frightening, and public. When that happens, even if the objective harm is limited, the public response will register as a crisis of trust.

History shows that losses of trust often appear as consequences of failures in governance, containment, alignment, or deliberate misuse — not sudden revelations about technology itself. That asymmetry is the lesson of the Three Mile Island accident of 1979, where a partial nuclear meltdown released only small amounts of radiation, and caused no immediate deaths, but created an outsized response.

On a risk-adjusted basis, it was a relatively low-cost event, but it was public, opaque, and terrifying. Operators appeared overwhelmed. Systems were poorly instrumented. Communication failed. The result was not a proportional response to risk, but a collapse of public permission. Nuclear progress stalled for decades because institutions failed to contextualize failure and manage fear — not because the technology was uniquely dangerous.

When we consider AI and the potential for failure, we should be precise about what that next incident is likely to look like. It will not resemble science fiction. More plausibly, it will involve:

A system behaving exactly as designed, yet misaligned with human intent:

Consider a hypothetical national health insurer that deploys an AI system to standardize care approvals and reduce unnecessary procedures. The model performs well — costs fall, variance shrinks. Then journalists discover that hundreds of patients across multiple states had chemotherapy, cardiac procedures, or neonatal care delayed or denied because the model optimized for population-level cost efficiency rather than individual medical urgency. No malfunction. No rogue model. But the human intent — to provide care first and manage costs second — was quietly reversed at scale.

A governance breakdown where responsibility is fragmented or unclear:

Imagine a government agency rolls out an AI system to help allocate disaster relief after a major hurricane. Aid is delayed for weeks in several regions. Local officials blame the federal algorithm. Federal agencies blame contractors. Contractors point to incomplete data. Congressional hearings follow — and no one can explain, in plain language, why help didn’t arrive.

A containment failure that allows a small error to propagate:

If a cloud provider’s AI-powered traffic optimization system misclassifies a routine software update as a security threat, the resulting problems could ripple far into daily life. In response, it could automatically reroute and throttle traffic across critical services — payments, logistics, emergency dispatch — pushing millions of users across multiple countries “offline” for hours.

Deliberate misuse by a bad actor:

During an election cycle, if a coordinated group uses generative AI to flood social media and messaging apps with hyper-local, highly credible deepfake videos of election officials announcing polling place changes, the fallout could be massive. The misinformation could be corrected within a day, but voter turnout might drop measurably, lawsuits could follow, and confidence in the election results may not be restored in timelines that matter.

Critically, in each of these cases, the perceived risk may vastly exceed the actual harm.

The downstream cost of the Three Mile Island accident is often overlooked. Energy demand did not disappear. Instead, it was met largely by coal and natural gas. Over the following decades, the world burned hundreds of billions of tons of coal, contributing to air pollution responsible for millions of premature deaths and to greenhouse gas emissions that now define the climate crisis. In hindsight, the alternative to nuclear power proved far more damaging — both to human health and to the planet — than the technology that triggered public fear in the first place.

Most experts (even the most fear-mongering) agree that we are fairly far away from an AI-driven catastrophic failure. But we are certainly not far away from a failure big enough to frighten the public, one complicated enough to be difficult to explain, triggering a reaction wildly disproportionate to the damage done. On a risk-adjusted basis, AI systems may still outperform human-led alternatives, but that may not matter.

Every foundational technology pays a tax during real-world deployment. The question is not how to eliminate failure — that is impossible — but how to limit its cost, explain it clearly, and prevent a low-damage, high-visibility incident from freezing progress altogether.

3. The Human Renaissance

In 2026 people will spend, per capita, more time outside and in physical communities.

One reason for this shift is growing frustration with the proliferation of “AI slop” across the internet. The other is our realization that screens are making us all feel terrible.

The developed world is getting very close to finally, collectively, pointing to the screen (and our addiction to it) as the principal culprit of our recent decline in happiness. The fight against screen time, especially among youth, will lead to a renewed interest in the physical world.

As Jonathan Haidt famously detailed in The Anxious Generation, the attention economy’s “rewiring” of our minds has triggered a global mental health collapse. We are digitally saturated but socially starving. Reports from the U.S. Surgeon General and the World Happiness Report link smartphone ubiquity directly to skyrocketing anxiety and loneliness.

We know how to solve this, because we know what makes us happy. The Harvard Study of Adult Development proves that face-to-face relationships are the primary predictor of health, while evolutionary psychology confirms our nervous systems are designed for complex natural terrain, not scrolling feeds.

In 2026, we will see a rise in real life, physical experiences. We’re already seeing the start of this trend. Pollstar’s 2025 Analysis shows that while live music ticket prices stabilized, crowd density exploded — Top 100 Worldwide Touring Artists sold an average of 19,104 tickets (up 11.9%), an all-time record. The Broadway season defied all expectations with a historic $1.89 billion gross, and MLB attendance grew for the third straight year, drawing 71 million fans.

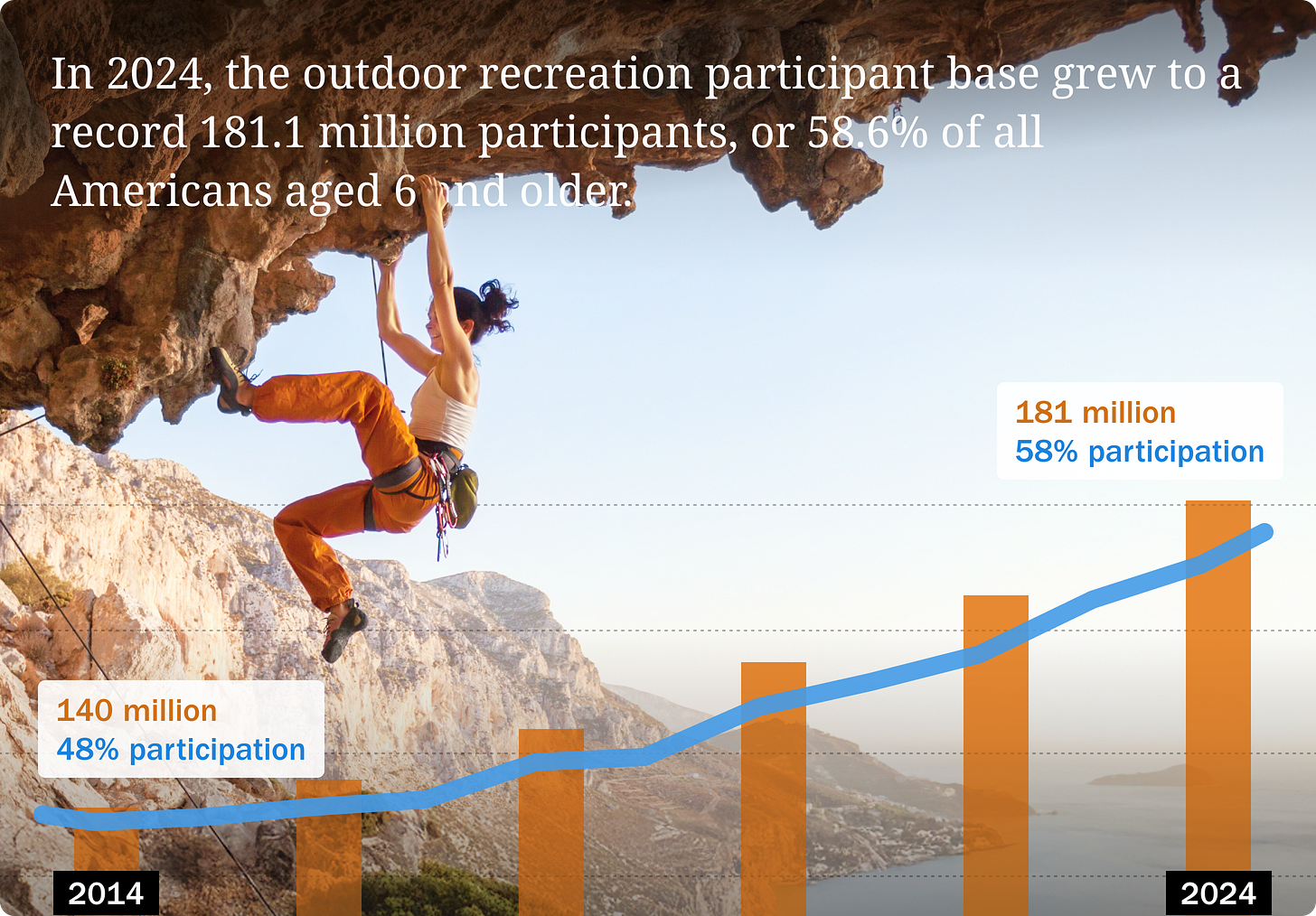

People are turning to the outdoors at record numbers; 181.1 million Americans reported recreating outdoors — 58.6% of the U.S. population — and the National Parks reported a record-breaking 331.9 million visitors in 2024 (our latest full year with visitor stats).

We have a human drive for community and the outdoors, and in 2026 we’ll return to it. My call to you is to support this movement by telling your local politicians that we need new parks, safer bike lanes, and true “third places” where people of all ages can gather safely and freely — ensuring that the antidote to digital isolation remains accessible, public, and human.

What Can You Do

With these trends in mind, I want to offer three strategies for moving forward in 2026, working with AI, and not losing the qualities that make life worth living.

Tell Stories About a Better Future: Pilots and racecar drivers use the term target fixation to describe the phenomenon that says the more you look at something, the more likely you are to move towards (or into) it. Acknowledge the danger, and look towards the safe, abundant paths ahead. We create the futures we imagine. Aim at the good ones.

Agency is Your Superpower: Personal responsibility is quickly becoming a major determinant of success, as more and more people have access to more supercharged tools and technologies. In an era of unmetered intelligence, the advantage belongs to those who choose to care, take responsibility for their growth, and act.

Be Human: You can’t beat a machine on its terms. As they get better at analysis, prediction, and execution, invest in stubbornly human attributes: courage, compassion, curiosity, humor, wisdom, and hope. These are our new advantages. And life is better that way, anyways.

Visit zackkass.com to learn more about Zack and get in touch.

1. Like the Escherish image.

2. Remember 3 mile island and this is a great example to weave in.

3. Love this article, thank you. The overall premise is so timely and relevant and the takeaways + reminder that being human has advantages. I've been saying to people worried about AI taking over music, movies and art - "there are thousands of directors and one Tarantino, AI isn't going to create the magic that Tarantino does, ever. Same with Gaga."

Brilliant Zack 💡👍