Discovering the Automation Boundary

In a future where everything can be automated, where will we stop?

If you could automate everything, where would you stop?

I regularly ask this question to audiences, friends, and business leaders.

Often, the first answer is a long pause, then a (knowing and hoping-you-don’t-imagine) laugh.

Once you get past the crude answers (which are better with friends than parents), the exercise is illuminating.

It’s easy to say what you want automated: that you hate email, that filling out the same form at the doctor’s office over and over again is maddening, that you want the airline to know (after so many flights) that you prefer an aisle seat.

But when people start talking about things they’d preserve — walking their kids to and from school, baking bread, practicing the violin — those answers reveal deep truths about each of us. They show what people care about — the challenges, annoyances, struggles, and experiences that give meaning rather than distracting from it, the ephemera of our lives that actually make up the core of it.

After giving their answers, I find that often, business leaders and parents turn the question back on me, “Well, what should I automate?”

The actual answer will differ for every person and business. But to help make sense of the question, I ask them to consider automation through this framework:

Does this enhance human agency?

Does it deepen trust and connection?

Does it sharpen human judgment?

Does it expand collective opportunity?

Can its outcomes be audited or reversed?

By answering these questions, we can begin to draw the line between those things we are comfortable automating, and those we want to remain in human control. I call that line the automation boundary.

Doing so successfully, and creating automation that amplifies our lives rather than hollowing them out, requires determining what friction in our life is vicious, what is virtuous, and what solutions should be left to humans.

The Miracle of Automation

History shows us that over centuries automation has proven to be one of the most consistent ways we have found to improve human life — even if it often comes in tandem with economic upheaval.

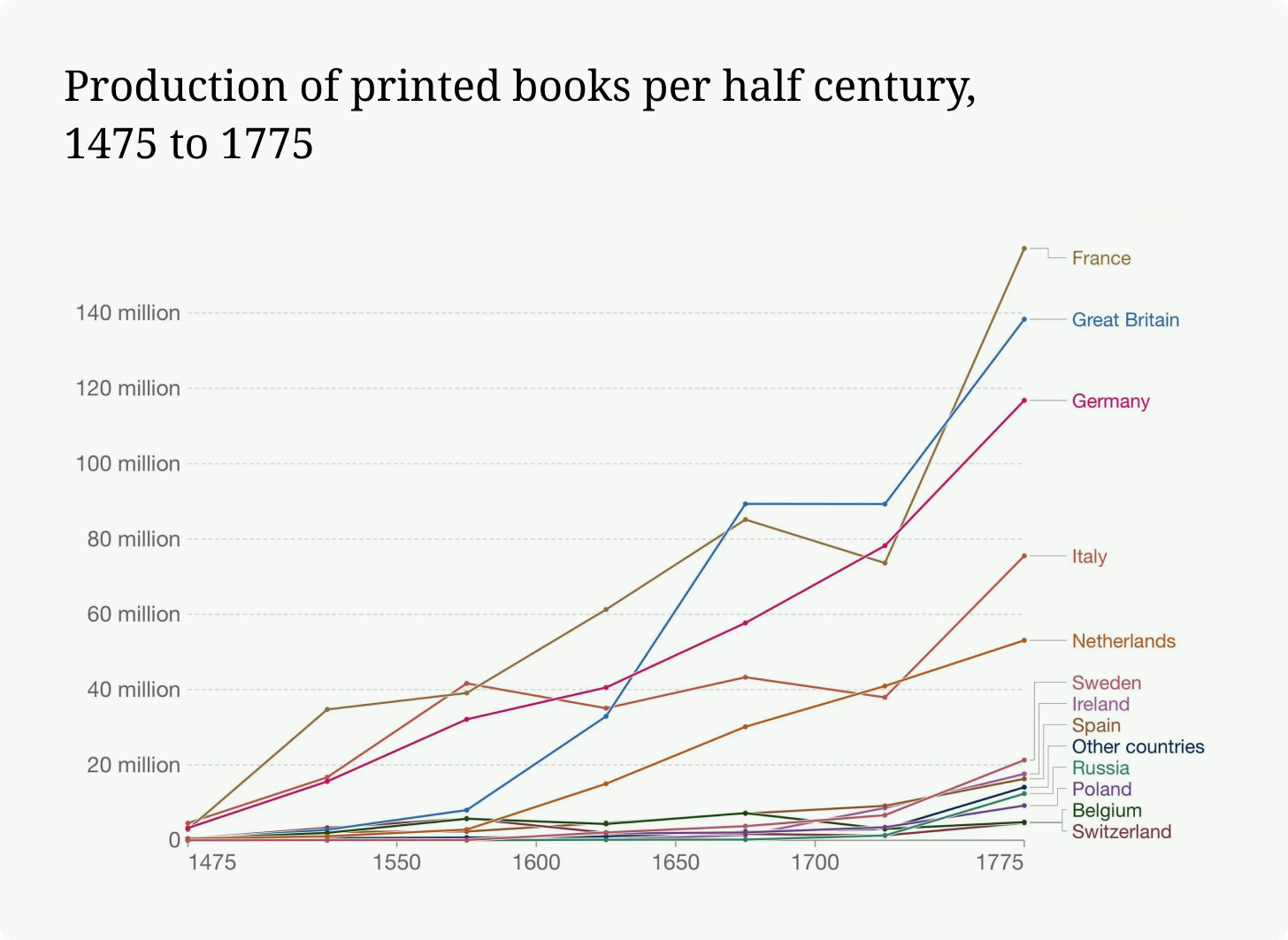

Before Gutenberg created his printing press, the number of manuscripts in Europe, hand copied by scribes, numbered in the thousands. A scribe could copy a few pages a day. The printing press could copy 3,600 pages a day. By 1500, about five decades after the printing press, there were more than 9 million manuscripts across the continent.

Textile mills reduced the price of cotton cloth by nearly a third between 1770 and 1801, and another 50% by 1815, making clothing affordable for the masses (and allowing regular people to take part in fashion, a pleasure long confined to the elites).

In 1900, families spent about 40% of their budget on food. By 2020, through mechanized farming, that number fell to less than 10%.

These strides often came with economic upheaval (mechanized farming shrunk the work necessary to feed the American population from 37.9% of the workforce in 1900 to 1.1% of the workforce in 2017), and this upheaval often brings waves of resistance.

Filippo de Strata, a 16th century monk and scribe complained to a chief magistrate about the arrival of the printing press saying, “They shamelessly print, at a negligible price, material which may, alas, inflame impressionable youths, while a true writer dies of hunger.” The Luddites smashed textile mills in an attempt to preserve their jobs and slow the pace of change.

In October 2024, 50,000 dockworkers walked off the job at ports along the American East Coast calling for a ban on automation, even though it would improve the safety of their jobs (which have a fatality rate nearly 5x the average American job).

Often, this pushback focuses on the economic impact of automation, rather than on the benefits it brings. But throughout history, access, affordability, and safety have won out. The cost of living depreciates, the number of things we can enjoy increases, and fewer people are injured and maimed in the process.

Automation has long improved life.

But today, I believe we are reaching its limits (or at least finding the edge).

The False Promise of Total Automation

The temptation of automation is to remove any inconvenience, struggle, or annoyance. AI and emerging technologies are making this future seem possible; it is not hard to imagine a Seussian (or Rube Goldbergian) future where automation makes life easy. Where machines cater to our every need and existence is contentment and relaxation. But as any teacher or coach will tell you (often during conditioning) there is value in hard work.

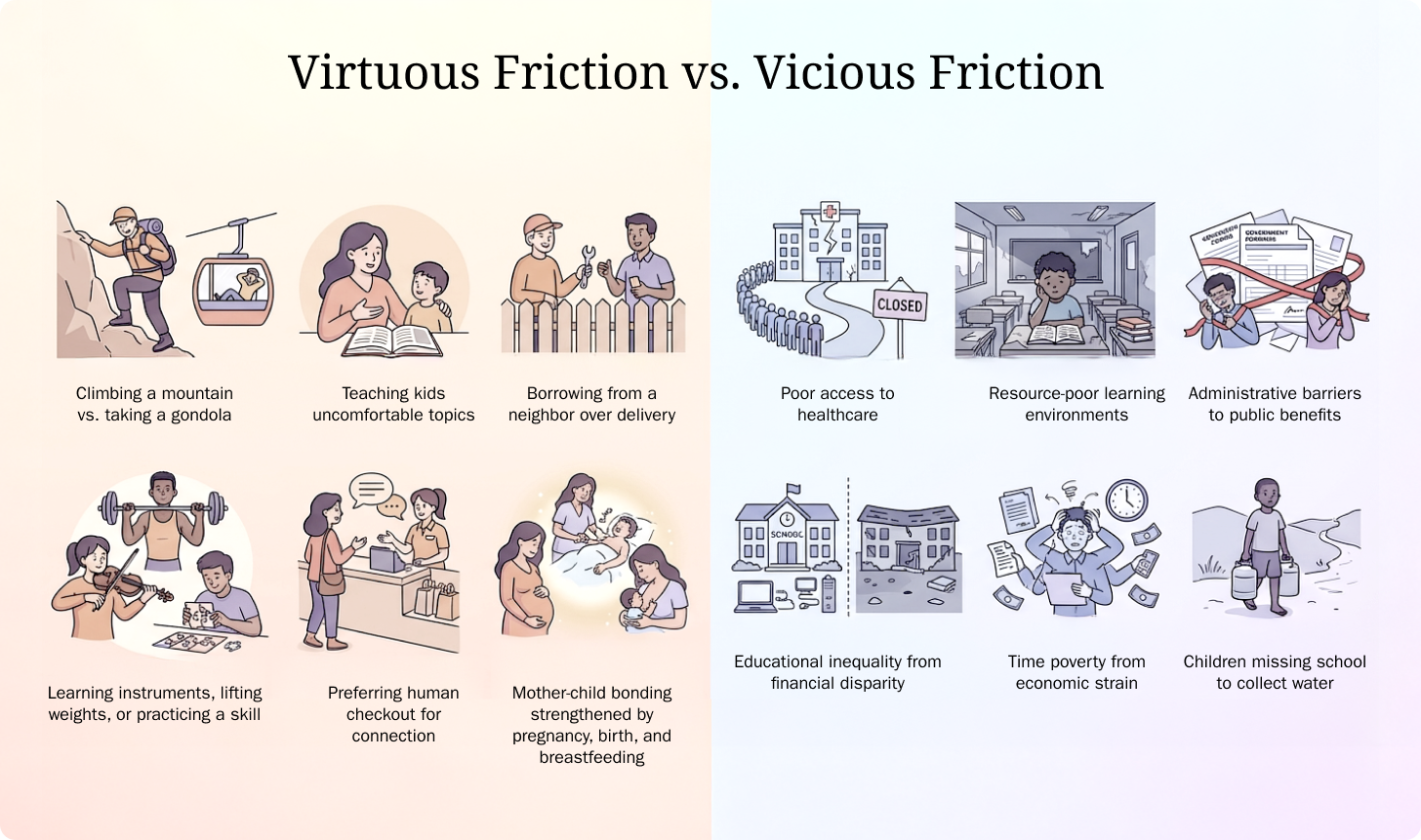

Some challenges beat us down. Some help us build ourselves up. I differentiate the two as virtuous friction and vicious friction.

Virtuous friction is the type of challenge that helps us grow, helps us connect with others, and provides defining human experiences. These challenges cultivate meaning and mastery.

Climbing a mountain is not the same as taking a gondola to the top. Teaching your kids the birds and the bees is uncomfortable, but it builds trust and a sense of safety. It’s easier to DoorDash a pound of sugar, but Mrs. Ogden will be so glad you knocked on her door and asked to borrow a cup.

In Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control, researchers showed that working hard to overcome struggle teaches you that hard work improves your capability, and gives you a means to improve yourself. Students who overcome struggles reading are more likely to see themselves as capable readers.

Learning an instrument, weightlifting in a gym, teaching yourself to freestyle rap, even when it comes with the potential for embarrassment (not a personal anecdote, don’t worry) add joy and color to our life. Research shows that each of us, intrinsically, seeks out challenges because we find them interesting and satisfying.

In some cases, human inefficiencies are the value-add, rather than the chokepoint to be automated away. It is the reason why so many of us have such a distaste for self-checkout. We want the human connection, the conversation, being recognized and valued, even if it means waiting in line behind four carts instead of breezing through a self-checkout with only our two onions.

And crucially, some struggles connect us more deeply to what it means to be human. Science is beginning to show that enduring pregnancy and childbirth adds value to both the mother and child’s life. Natural labor, birth, and early breastfeeding are associated with surges of oxytocin, which is linked to maternal caregiving, stress reduction, and bonding behaviors. Some newer physiological reviews are even exploring if labor and birth causes long-term adaptations to the oxytocin system, further influencing the mother and child interaction.

Vicious friction, on the other hand, is the type of challenge that only diminishes our lives. These hold us back, prevent us from growing, and isolate us from our peers and opportunities.

There is little to be gained from being unable to reach a doctor, not having access to warm and safe environments to learn and grow, or access to utilities that make hygiene the standard.

An overwhelming onslaught of administration that prevents people from accessing (let alone applying for) public benefits does not lead to growth; it keeps families from realizing the assistance meant to help them.

Financial disparity that creates inequitable access to education (often through differences in property taxes) does not teach children to work through educational challenges; it creates artificial burdens that limit opportunities.

Time poverty, often mediated by lower socio-economic status that requires heads of house to spend more hours working to support a family than they spend with them, does not build stronger social bonds; it only compounds existing economic disadvantages.

Frustration that comes from sounding out a difficult word in a second-grade classroom is beneficial. The difficulty of not being able to go to school because you have to walk to gather water is anything but (around the world, women and girls spend 200 million hours a day collecting water, cutting into time for education).

The automation boundary should protect virtuous friction, and eliminate vicious friction.

The Danger of Dehumanization

While we consider what challenges we want to preserve, we should also consider the solutions we don’t want to replace (at least not with a machine). In 1984, Pope John Paul II wrote, “Human suffering evokes compassion.” While eliminating suffering is a just goal, it is crucial to consider solutions that build compassion as well. I argue that many of these solutions should be human, even if AI tempts us with machine speed and efficiency.

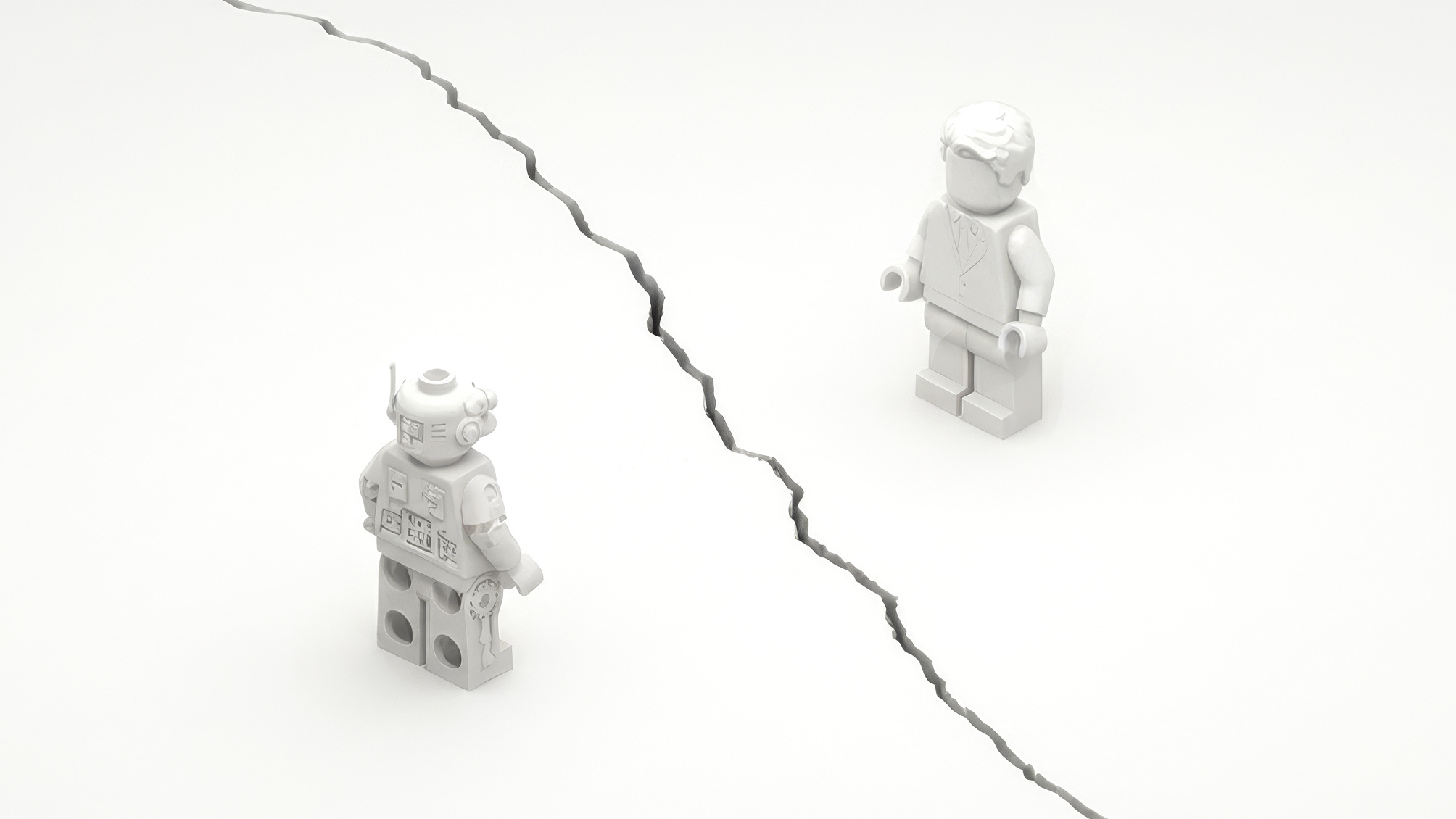

If we turn to machines too rapidly and absolutely, we are in danger of what I call dehumanization: the process by which individuals prefer digital lives and interactions to human ones.

Studies show that treating loneliness with AI companions can cause people to replace human relationship with digital ones. Researchers are already strongly recommending against sending teens to AI for mental health support. Therapists are raising the alarm that going to AI instead of human therapists can cause emotional dependence and increased anxiety.

Automation risks causing humans to turn away from connecting with each other and toward insular experiences mediated by computers. The consequences are already arriving in the form of AI psychosis, and the results are dire.

Social isolation can be as dangerous as smoking 15 cigarettes a day, but synthetic connection can deepen the problem.

Finding the Automation Boundary

We are quickly reaching a point with AI automation (as we are in so many AI-related fields) where “can we” is not a sufficient question. My heuristic provides the next five:

Does this enhance human agency?

Does it deepen trust and connection?

Does it sharpen human judgment?

Does it expand collective opportunity?

Can its outcomes be audited or reversed?

By accurately answering these questions to determine the automation boundary, we can eliminate vicious friction, preserve virtuous friction, and realize the responsibility of directing our increased time, energy, and awareness (as provided by AI) towards solving those problems that demand, and deserve, human solutions.

Visit zackkass.com to learn more about Zack and get in touch.

What struck me in this article the automation conversation is reframed from technical capability and toward human intention. The exercise of asking what we want to automate and, more importantly, what we would never automate forces leaders to confront the difference between tasks that drain us and tasks that define us. The automation boundary framework is one of the clearest tools I’ve seen for separating efficiency from meaning. In a time when AI can remove almost any inconvenience, we are reminded here that some forms of friction are not just acceptable; they are actually essential to agency, connection, and growth.

The article well demonstrates that automation can deliver gains in access, affordability, and safety. Except there is a warning label folks: eliminating the wrong struggles, risks hollowing out parts of life that create capability and community. The distinction between virtuous and vicious friction can help us as individuals and leaders to think more responsibly about where AI should accelerate processes and where it should intentionally stop. This balance, of leveraging automation without drifting into dehumanization, is the nuance we need right now, and it is well articulated here, with rare clarity.

I enjoy the historical stats Zack includes in these newsletters. They give helpful perspective on our current opportunities and challenges.